Meet the Man Fueling Clean Energy Opposition in the Midwest

Kevon Martis and a group of fossil fuel-funded allies have led a decades-long campaign to sow fear and misinformation about renewable energy. It’s working.

This is a special joint edition of Distilled and HEATED, a newsletter written by journalist Emily Atkin. HEATED is a must-read for anyone who cares about holding polluters accountable for the climate crisis. Sign up HERE.

Last year, Heather Hodge heard about a proposed clean energy project in her rural Michigan community. Not too long after, things started to get ugly.

It started in October 2022, when Hodge—who works for a biotechnology lab in nearby Lansing—heard about a proposed utility-scale solar farm in the townships of Conway and Cohoctah. If built, the project would provide enough clean electricity to power about 30,000 homes.

“I'm thinking, ‘Oh, solar is coming through, it's gonna be a done deal,’” Hodge told HEATED and Distilled. After all, 90 percent of Michiganders support solar energy, and only three percent strongly oppose it. And her area had a history of approving local energy projects.

But as she began expressing excitement about the project, Hodge found that some of her neighbors were fearful. At a local high school basketball game, someone told her the project could give her cancer. Shortly after that, Hodge saw a Facebook post from a local parent claiming it would dramatically reduce property values.

Then, at the first public hearing in December, Hodge read that only five out of the 40 people that spoke about the solar farm were in support. And in addition to fears about property devaluation and cancer, multiple residents said they were worried that the solar farm would contaminate the water supply. One woman argued the panels would engulf birds in flames.

Fear and misinformation in Michigan

Hodge, a scientist by training, began looking for data to back up the claims. She soon discovered that most people’s fears were unfounded.

No peer-reviewed research linked solar panels with cancer. Three peer-reviewed studies concluded that solar farms don’t impact property values. A concentrated solar farm in the Mojave Desert had burned birds—but the proposed project in her area was a photovoltaic farm that doesn’t get that hot. And no studies have found a link between solar farms and water contamination.

But Hodge’s neighbors still seemed to be getting even more fearful—and angry. So she attended the next public hearing on January 5.

That hearing, she said, was even more heated than the first. The large crowd booed and heckled a local member of Sierra Club Michigan, Mike Buza, who spoke in support of the project. “I was terrified [to go up and speak],” Hodge said. But she managed to go up and express her support.

Afterward, Hodge said three men angrily stared at her. “Each one was like, yeah, that's the traitor,” she said. Hodge also saw another man follow Buza out of the room, before accusing him of being a paid actor and saying God would punish him for what he had done.

The anti-renewable crusade of Kevon Martis

Following the meeting, Hodge reflected on the experience in confusion. Why did so many of her fellow community members believe this solar farm would cause cancer, contaminate their water, and destroy their property values? Why had so many people turned out to these meetings? And why was everyone so angry?

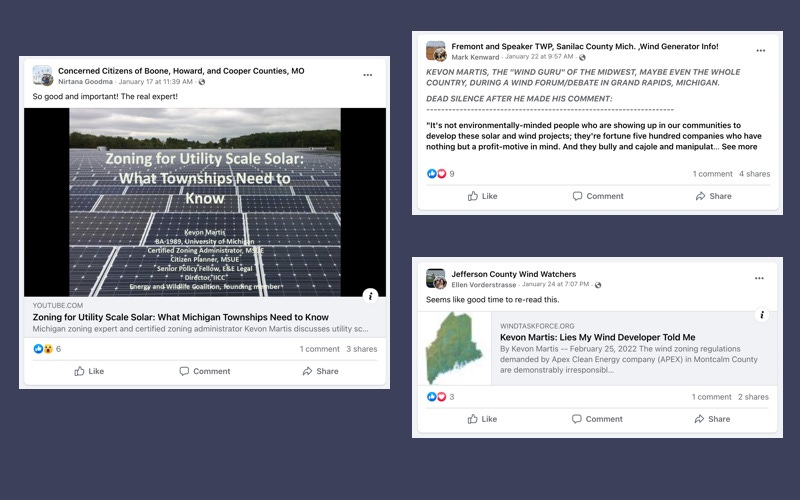

Hungry for answers, Hodge went on Facebook, where she discovered multiple groups dedicated to opposing the project. After joining the groups, she found they were full of articles and claims made by the same person: Kevon Martis.

Hodge didn’t know it at the time, but she had accidentally discovered the public face of one of the most influential anti-renewable efforts in the country.

Aided by a small group of allies—many of whom receive money from the fossil fuel industry—Martis has helped pass dozens of laws that ban or severely restrict clean energy development in towns and counties across the Midwest. In order to pass these laws, he’s used misinformation and fear-based tactics that wind up dividing entire communities.

Though Martis’s crusade hasn’t been covered much by national media, clean energy advocates say it’s actively hamstringing the fight against climate change in the Midwest.

A clean energy executive told HEATED and Distilled that if Martis gets to a community before them, their projects are almost certain to be blocked by the local government. The executive asked for anonymity in fear of being targeted by Martis.

A personal dispute sparks a decade-long war

Martis declined to be interviewed for this story. In an email to HEATED and Distilled, he expressed offense at being described as an opponent of clean energy. “Objective ‘journalists’ don't lead with insulting pejorative phrases like ‘opposition to clean energy,’” he wrote. At the bottom of the email he added “#fail #bias”.

But according to multiple residents of his small town in Michigan and a former local government official, Martis’s anti-renewable crusade began as a relatively mundane personal dispute. John Tuckerman, a Lenawee County Commissioner from 2003 to 2015 who has known Martis for more than a decade, said Martis was running a small construction company in Riga, Michigan in 2010, and wanted to rezone a part of the town to build new homes.

But Martis was overruled by the town planning commission, Tuckerman said, and shortly afterwards the commission approved plans for a wind energy project on the land.

“He was angry,” said Tuckerman.

Shortly thereafter, in 2011, Martis and a group of people in town formed Interstate Informed Citizens Coalition (IICC), a nonprofit dedicated to fighting clean energy projects. Martis’s co-founder at IICC, Joshua Nolan, represented Martin County Coal Corporation in a lawsuit that same year.

Disinformation was a key part of IICC’s strategy from the beginning. As a part of their first campaign, the group bought a TV ad that claimed a proposed wind farm in southeast Michigan could “harm your families’ health, significantly reduce property values, and damage TV and radio signals, possibly depriving your family of important safety alerts.”

The misleading ad helped IICC secure its first victory. In July 2011, Riga passed one of the country’s most restrictive wind turbine ordinances, effectively banning wind energy projects in the area.

Martis quickly expanded the campaign, eventually helping pass similar ordinances in nine other towns and counties. But his work was only just beginning.

Martis meets with climate deniers — and his impact grows

The following year, Martis attended an event in Washington D.C. with some of the country's most influential climate deniers. There, he swapped ideas with organizations like the Heartland Institute and Americans for Prosperity, which receive much of their money from the fossil fuel industry.

According to a leaked document from the event, Martis’s objective in attending the event was to “seek funding for lobbying efforts in Lansing.”

It’s unclear whether or not Martis found any funding. (Neither Heartland nor Americans for Prosperity returned a request for comment). But shortly after, IICC successfully helped block a law that would have required utilities in Michigan to generate 25 percent of their energy from renewables by 2025.

Martis and IICC also started paying witnesses thousands of dollars to testify against a renewable portfolio standard in Ohio, according to a leaked email obtained by Energy and Policy Institute. That clean energy law eventually failed as well.

Martis and IICC also began increasing the temperature of their attacks against environmentalists. At a 2013 wind energy conference, he and another IICC member dressed up as a “Big Green Lie” and “Death Turbine” to convince people on the street that wind energy was dangerous.

When Peter Sinclair, a clean energy advocate in Michigan, criticized Martis in a letter to an editor, Martis edited a picture of Sinclair’s face onto the body of a doll and posted it to Facebook. Martis has done this to multiple opponents.

Today Martis serves as a County Commissioner in Lenawee County, a position he’s held since last summer. He continues to run advertising campaigns asking residents to block solar and wind projects and regularly spreads misinformation on Facebook.

He’s also a senior policy fellow at E&E Legal, which has received funding from coal companies like Peabody Energy and Arch Coal. The think tank is best known for its infamous attacks on climate scientists and its widespread climate denial campaigns.

Anti-renewable hatred gets violent

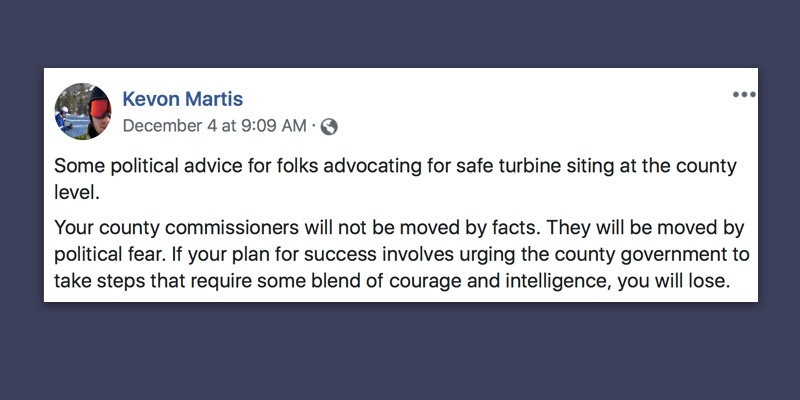

Martis has said his overall strategy is to sow fear among pro-renewable politicians. In a recent Facebook post, Martis wrote, “Your county commissioners will not be moved by facts. They will be moved by political fear.”

But it’s not just politicians who have been moved by Martis. Communities are now at each other's throats.

Tuckerman, the former Lenawee County Commissioner, has attended town meetings for decades. Before Martis showed up, he said town and county meetings were rarely contentious. But all of that changed after 2011 when IICC launched, he said.

Suddenly, Tuckerman said he and other elected officials began to receive threats when they voiced support for clean energy projects. He said farmers who signed leases were regularly called out in public meetings and verbally harassed.

In a 2020 Facebook post, Martis wrote, “The true cost of 40-50 or 60% wind generation in any given state must include the cost of a new Capitol building.” The post included a picture of a burned-out truck that anti-wind activists in Australia destroyed in a protest. E&E has not returned a request for comment about the post.

This kind of rhetoric has permeated the tone of public hearings on renewables in Michigan. Buza, who says he has attended more than 100 town and county meetings, said it’s not uncommon for people to leave in tears now. On a few occasions, he said, supporters of clean energy projects have had to be escorted out to their cars by the police.

“The tone of it is a lot angrier, a lot more threatening,” he said.

Still, supporters of clean energy like Heather Hodge remain undeterred. In January, planning commissioners in her town voted to place a 12-month moratorium on solar development, killing the proposed project. But after the moratorium expires, Hodge said she plans to continue advocating for solar. She hopes other clean energy advocates will join her.