Severe Drought Erased Climate Progress in the Northwest in 2023

Power emissions rose in the region due to drier conditions and less hydro output

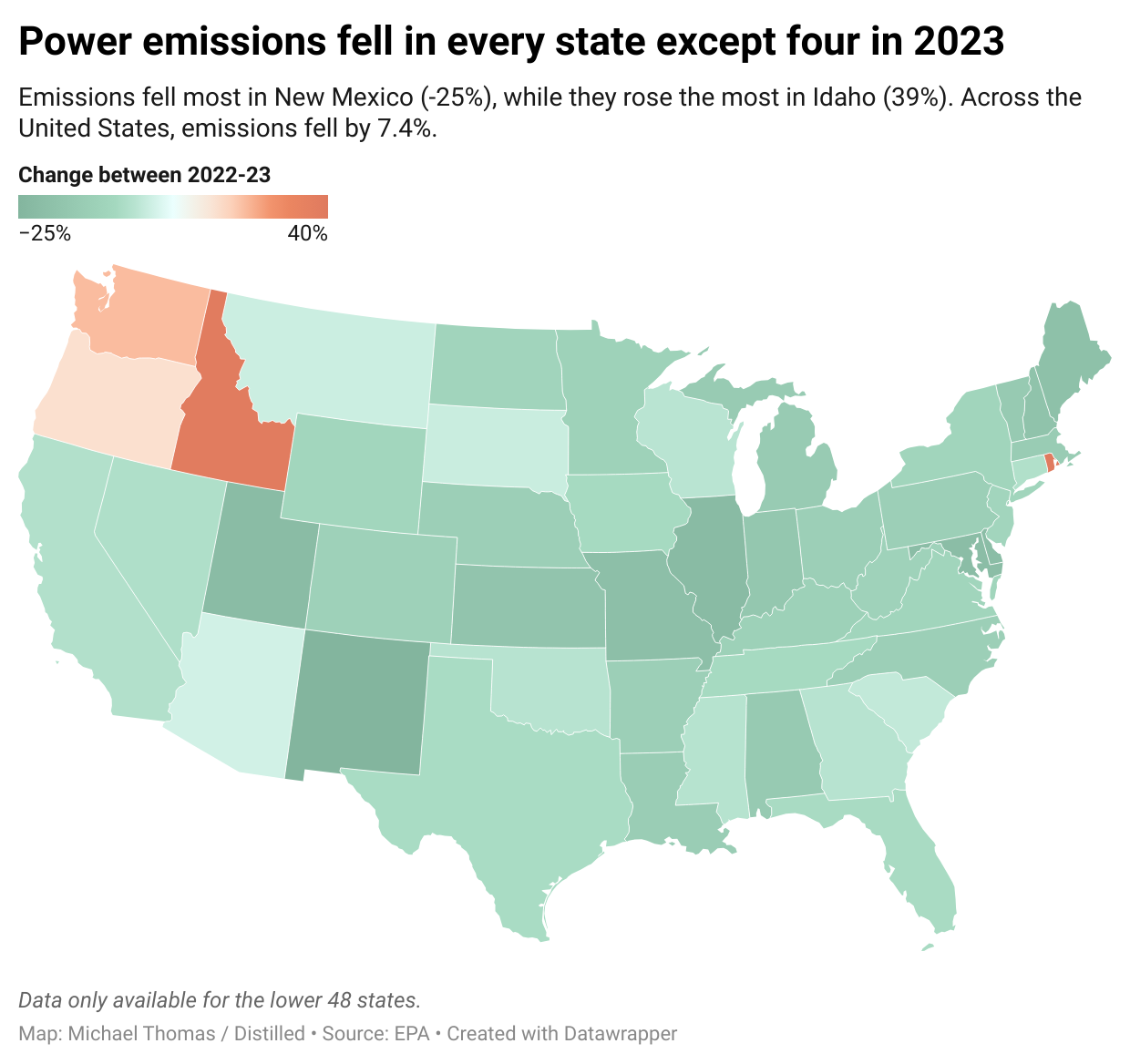

Last week, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released data showing that power sector emissions fell in the United States by 7% in 2023.

The announcement hardly made headlines because—let’s be honest—falling electricity emissions is old news. The U.S. is deploying record amounts of wind, solar, and batteries and retiring coal plants. This is good news, but it’s old news.

That’s why I was surprised when I noticed something strange in the data: Power emissions didn’t fall in every state.

Looking at a map of emissions changes across the states, it’s clear that something happened in the Pacific Northwest last year. That something was a feedback loop, a cycle in which climate change caused more climate change. And it’s part of a troubling trend in the Western United States.

Why emissions rose in the Northwest last year

The electric grid in the Northwest is unique in that it’s powered, mostly, by falling water. Hydropower is responsible for about two-thirds of electricity generation in Washington and about half of generation in Idaho and Oregon.

Renewables like solar and wind are frequently attacked by clean energy opponents for being variable resources. You can’t just turn on the sun at midnight or get the wind to blow on a still day. Hydropower, by comparison, is more “firm” than solar and wind—dam operators can, generally speaking, open the literal flood gates and get a turbine spinning within a few minutes—but over long periods of time, the total amount of power generated still depends on the climate.

Here’s the problem: Climate change is making droughts around the world more common. And that means hydropower, once the most reliable source of power in many regions, is becoming less dependable. Hydro plants are generating less power than they used to.

Last year, the Pacific Northwest was hit by severe drought. By August about half of the region’s land area was suffering drought conditions, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). As a result, less water flowed through the region’s rivers and dams. 2023 was the 4th worst water year on record since 1949, according to the Northwest River Forecast Center (NWRFC).

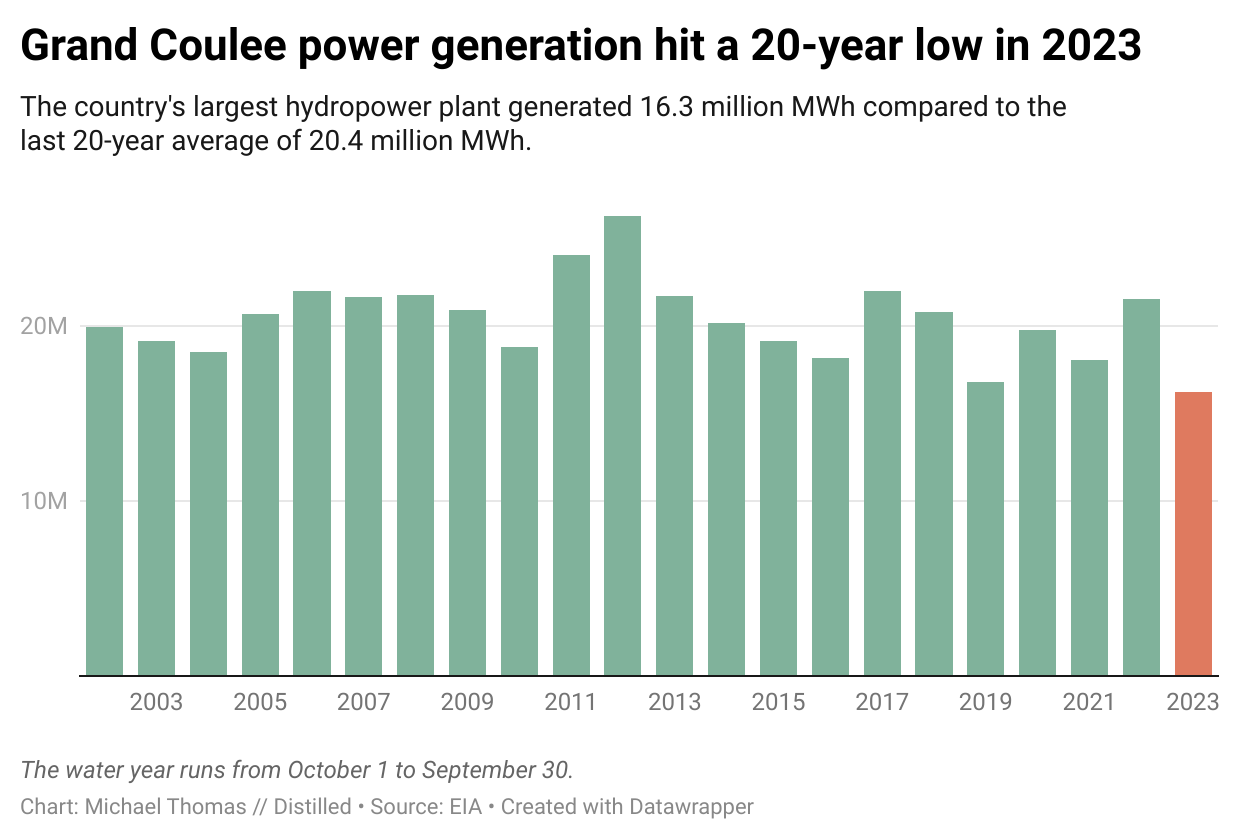

And in the Northwest, less water means less carbon-free power. Take Grand Coulee Dam, for example. The largest hydropower plant in both the Northwest and the country produced less power in 2023 than it did in any year over the last two decades.

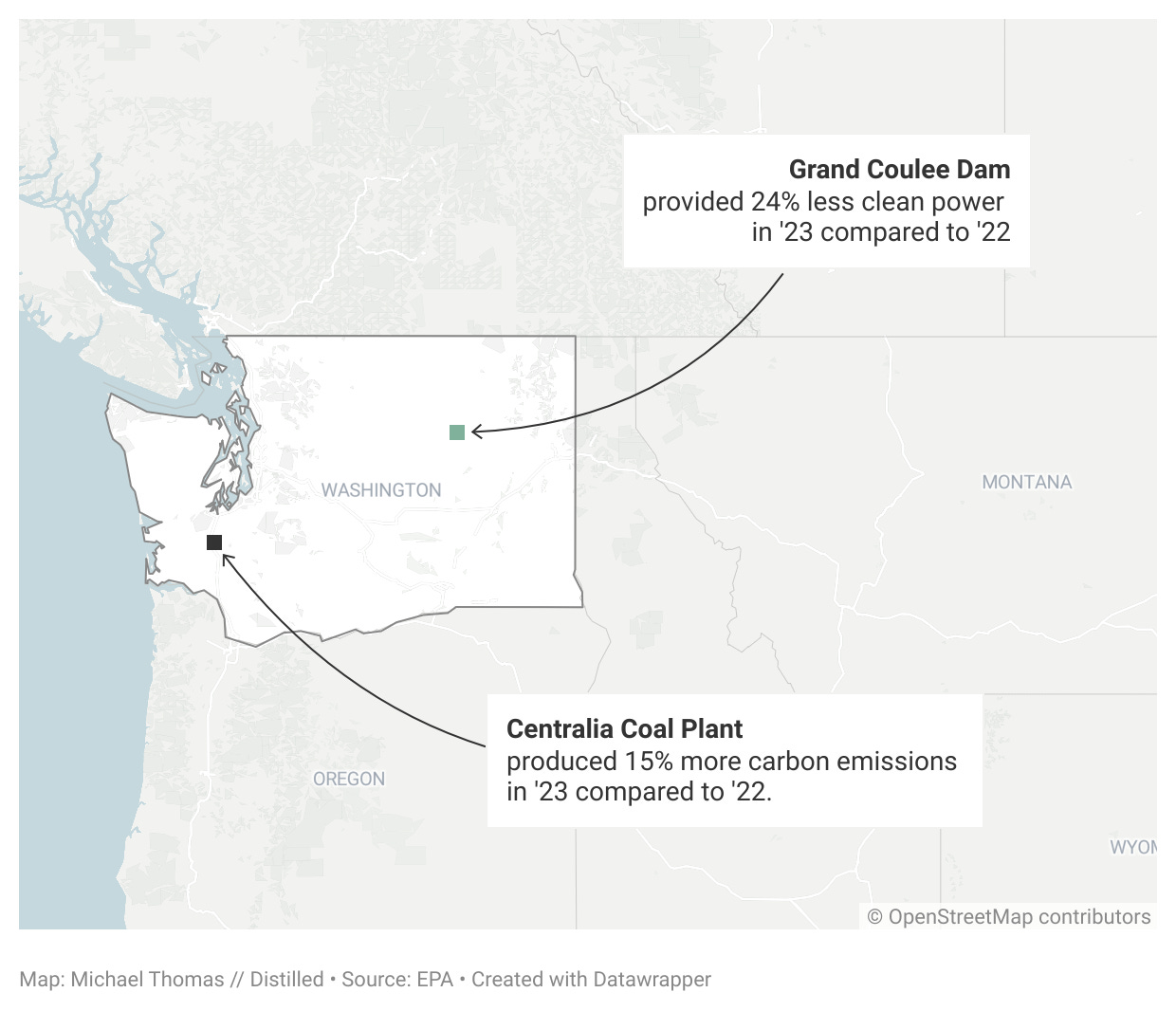

Grid operators in the region had to make up for the difference in electricity generation. So they turned to Washington’s only coal plant as well as the region’s many gas plants.

While virtually all coal plants across the country burned less coal in 2023 than in 2022— a continuation of their long-term trend—Centralia Coal Plant burned 15% more coal. Meanwhile, the average gas plant in the state burned 75% more fuel last year than the year before.

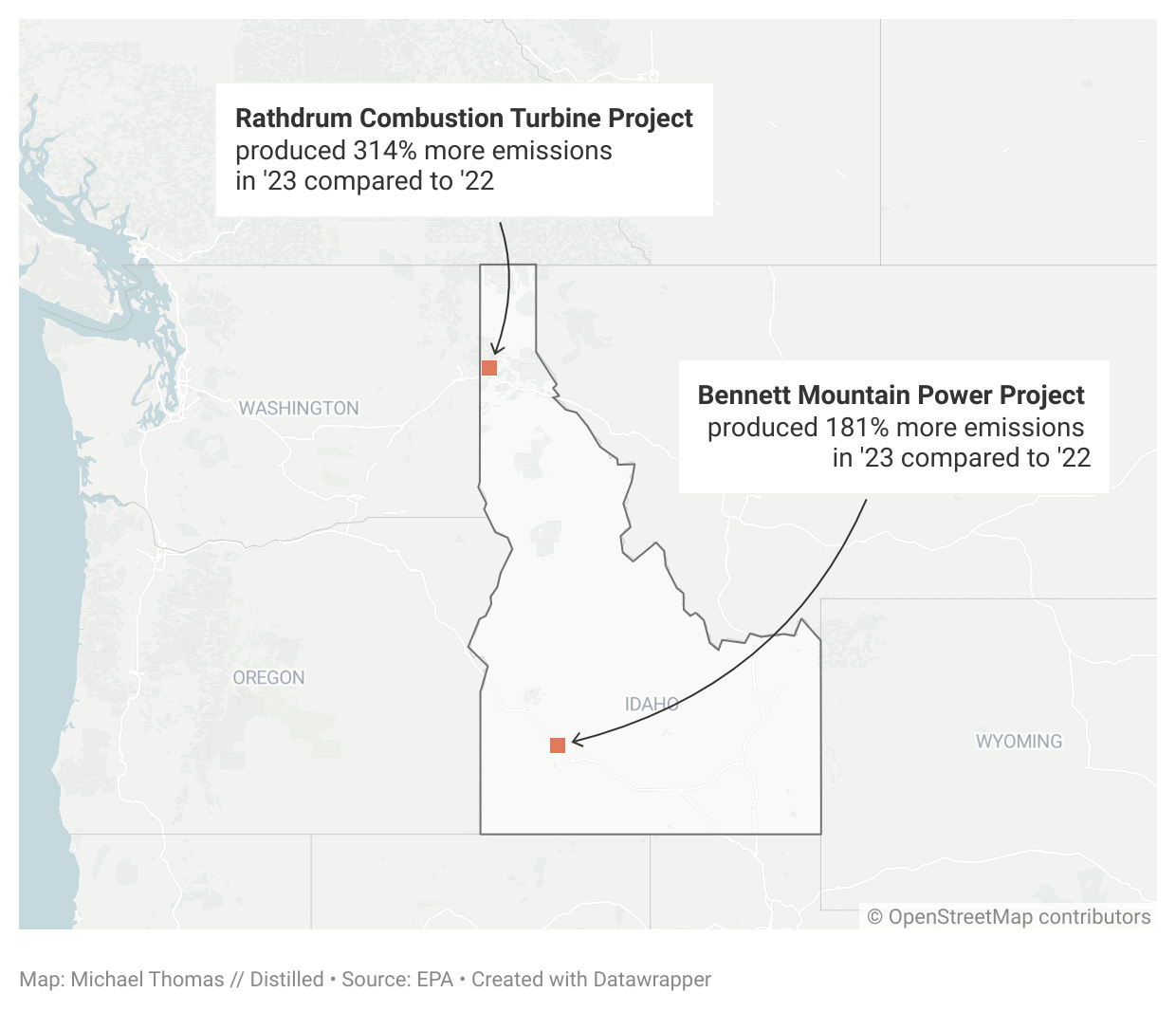

In Idaho it was a similar story. Hydro output fell, while power generation and emissions at the state’s two largest gas plants rose by 181% and 314%.

The drought didn’t just cost the planet. It also cost the average person in the region in the form of higher utility bills and worse air quality.

In October, Seattle City Light announced that it had burned through more than $130 million as a result of the hydropower shortages. To make up for its losses, it boosted utility bills by 4% for its 460,000 customers.

Wholesale power prices rose to a record $99 per megawatt-hour (MWh) in 2023 compared to their five-year average of $58 per MWh, according to data from the federal government and financial firm LSEG.

As coal and gas plants in the region burned more fuel, they emitted more harmful pollutants into the atmosphere. While NOx emissions fell by 15% across the United States, they rose by 17% in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho.

Droughts threaten carbon-free power goals

What happened in the Northwest this year was a part of a larger trend. Droughts in the Western United States have reduced hydropower output consistently over the last two decades.

Power generation from Hoover Dam in Nevada has fallen by a third in the last decade, according to Bureau of Reclamation Officials. At peak output, the dam can generate enough carbon-free electricity to power a million homes. In recent years, it’s generated enough to power 675,000 homes.

At one point in 2022—two decades into the Southwestern United States’ worst drought in more than 1,200 years—officials were warning that water levels could fall so low that Hoover Dam would no longer be able to generate any power at all, a level known as “deadpool.”

Across the Western United States, the decline in hydropower output caused by the megadrought has led utilities to burn more coal and gas resulting in 121 million tons of carbon emissions between 2001 and 2021, according to researchers at Stanford.

The pollution from that added fossil fuel power generation has caused $20 billion in damages, according to the same research.

Climate scientists are uncertain how precipitation and runoff patterns will change in the future. As a result, it’s difficult to predict how total hydropower generation might change over the next decade.

“While the models used by climate scientists generally agree on how different parts of the Earth will warm, there is much less agreement about where and how precipitation will change,” writes climate scientist Zeke Hausfather.

But virtually all climate models agree on one thing: The world of the 21st century will look very different from the world in which our dams, power lines, and cities were built in.

Want to support independent climate journalism?

Climate journalism is a rough spot. Established media outlets like The Washington Post, Vox, and CNBC have all laid off their climate reporters in recent months. Meanwhile, the fossil fuel industry is ramping up lobbying and misinformation to convince people that oil and gas is good for people and the planet.

I started Distilled to produce in-depth, independent climate journalism. Thanks to our paid subscribers, I’ve been able to do original reporting and data analysis, debunk climate myths, and make videos about climate change.

To support this work, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. For just $5 per month, you can make stories like this possible.

Washington in particular is disappointing because they have not been building other renewables, despite a supposedly climate-leading governor, and big electrification plans. It will be interesting to see some near-term decisions from their "siting board." There is a plan that the Biden admin seems to like to tear out a bunch of dams and build renewables to replace them, but the same tribes who want the free-flowing river seem to have problems with almost all proposed renewables. ("Green Colonialism!" Really.)

In Idaho, a perfectly reasonable windfarm is being held up by the now-usual exaggerated local objections plus the fact it can be seen (3ish miles) from a monument at a former WWII Japanese internment camp. Portland is buying wind power from eastern MT. And so on.

I'm not sure what the consumption trends have been in these states. I know lots of data center owners and others covet the use of their hydro for firming their "24/7 100% clean" targets.

Interesting article, but does not discuss the larger picture for the Northwest. Because of their abundance of hydro-power, British Columbia used to export excess power to the U.S. under the Columbia River Treaty. Today BC is importing approximately 25% of their energy needs because hydro-power production has decreased. Renewal of the Columbia River Treaty is currently under negotiation and could have a significant impact on hydro-power production and salmon in the NW.