The Loophole That Made Cars in America So Big

Here's why American cars and trucks are so big

This story is a part of a larger series on America’s changing transportation system. Check out our stories on the growth of the U.S. EV charging network and the rise of electric SUVs and trucks. And subscribe to receive more stories like this in your inbox.

You can also watch a video we made about the SUV loophole on our YouTube channel.

Few trends have been worse for the environment than the dramatic growth of the SUV market in recent decades.

Between 2010 and 2020, 65 million new SUVs hit the roads in America. Collectively those cars will pump about 4.4 billion tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere over the next few decades, more planet-warming pollution than most nations have emitted throughout their entire history.

But the dominance of SUVs on American roads is a relatively new phenomenon. In 1980, SUVs made up less than 2% of new car production in America; last year, that number was closer to 50%.

According to automakers, changing consumer preferences explain the growth of the SUV market.

In this telling of the story, the growth began in the 1990s when baby boomers demanded bigger cars for their growing families. SUVs like the Ford Explorer and the Jeep Cherokee were more expensive and less fuel efficient than sedans, but boomers didn’t care; they were the richest generation in history.

Then as millennials started families over the last decade, the growth continued. And that’s how we ended up in a world where SUVs and trucks make up roughly 70% of the car market.

“We’re providing the vehicles that consumers want,” Kumar Galhotra, Ford’s president for North America, told the New York Times recently.

But this story overlooks the crucial role that automakers played in shaping those consumer preferences. It overlooks the incentives that these companies had to build SUVs. And most importantly, it overlooks the policies that automakers lobbied for over the last 50 years to create those incentives.

The birth of the SUV loophole

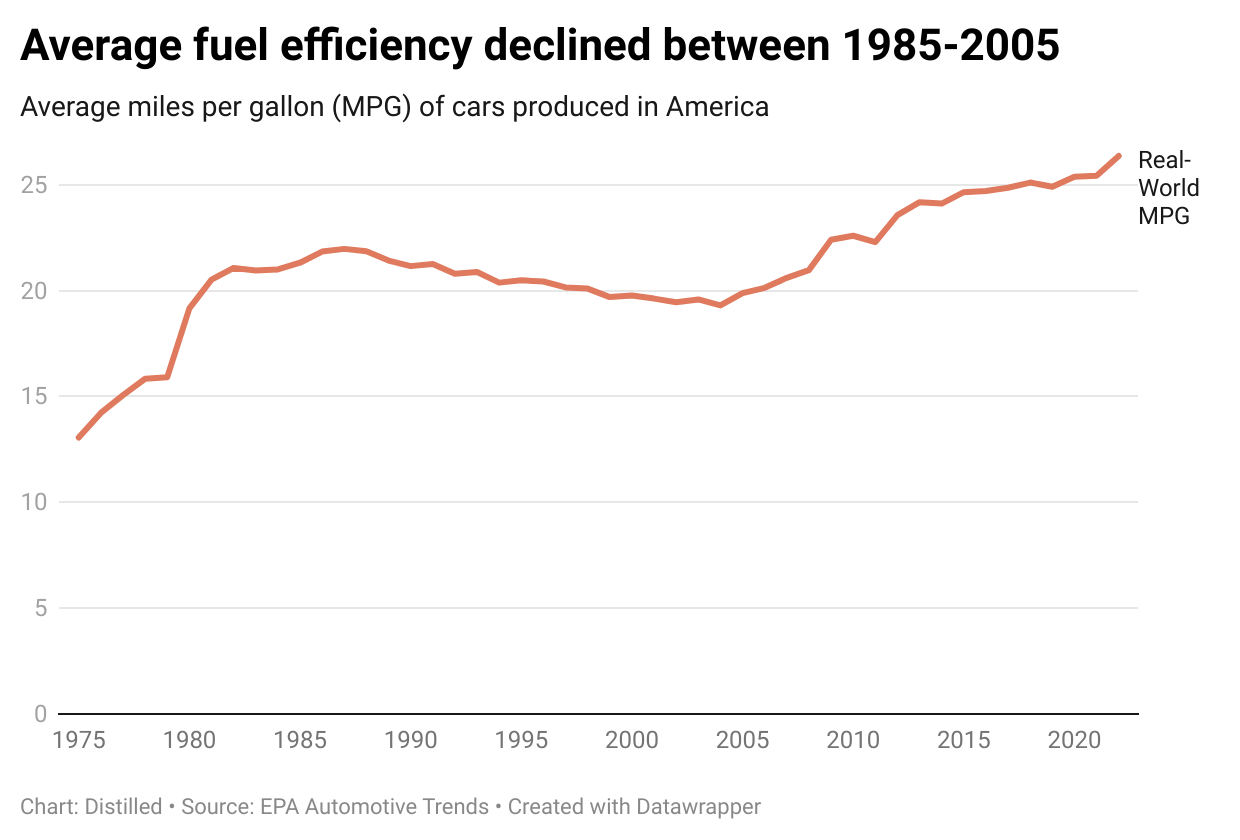

In 1975, Congress passed a law that forced automakers to double the average fuel efficiency of their vehicles to 27.5 miles per gallon by 1985. For a few years, the bill worked as intended. The average fuel efficiency of American vehicles went from 13 MPG in 1975 to 19 MPG in 1980.

But then something strange happened.

After leveling off between 1980 and 1985, average fuel efficiency actually fell over the next 20 years. It’s been a half century since Congress passed its first fuel efficiency standard and the average vehicle produced in America still doesn’t get 27.5 MPG. So what happened?

The short answer is that auto lobbyists happened.

The intent of the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975 was to make all passenger vehicles in America more fuel efficient. But auto lobbyists convinced regulators to make a subtle change to the bill’s text. While efficiency standards for cars would be written into the law itself, the standards for trucks were to be set by regulators at the Transportation Department.

As Keith Bradsher writes in High and Mighty: The Dangerous Rise of the SUV, “The automakers wanted any fuel-economy standards to be set by regulators, not by Congress. Their reasoning was based on the fact that once Congress passes a law, it is extremely difficult to undo it…Regulators could also be lobbied to set less stringent standards later.”

This proved to be a genius, if unethical, strategy. Out of the public eye, lobbyists were able to score regulatory wins that would have consequences for decades.

One of the first things that officials at the Transportation Department had to do was define what a truck was in the first place. Automakers convinced them to go with the vague definition of “an automobile capable of off-highway operation.” Thus, as long as an SUV had four-wheel drive and decent ground clearance, it could avoid the more stringent car regulations and instead be regulated as a truck.

Automakers also convinced regulators that any vehicle with a gross vehicle weight above 6,000 pounds should get a carve out. Their justification was that vehicles this big were made for commercial uses like farming, not shuttling kids to football practice.

When these emissions rules were first proposed, a third of vehicles produced had a gross vehicle weight of more than 6,000 pounds. In order to avoid regulations, automakers started producing heavier cars. By the time the rules were finalized and implemented a few years later, two-thirds of cars were heavy enough to avoid the regulations.

In 1978, faced with another oil crisis, Congress passed the “gas guzzler tax.” The idea of the law was to slap anywhere from $1,000 to $7,700 in taxes on vehicles that were well-below the minimum fuel efficiency standard. But lobbyists successfully convinced Congress to exclude the biggest gas guzzlers of them all: trucks. And because SUVs were trucks too, those got the carve out as well.

Thus in just a few years, automakers created what would eventually be known as the “SUV loophole.”

Automakers spent billions pushing SUVs

The SUV loophole significantly changed the economics of making cars and trucks in America. Due to their more stringent regulations, small cars became more expensive to manufacture. Meanwhile, trucks and SUVs became cash cows.

In the 1990s, Ford launched its Expedition, a tank of a car that got 14 miles per gallon, worse gas mileage than the average car got 20 years earlier. Thanks to the SUV loophole, the Expedition was wildly profitable for Ford, earning the company $12,000 in profit per vehicle.

That decade the big three automakers all launched new SUV lines. But they quickly ran into a problem: most people didn’t really need them.

Consumer surveys conducted by automakers at the time found that just a few percent of SUV owners ever took their car off-road. When they did it was likely to be on a paved dirt road.

“The only time those SUVs are going to be off-road is when they miss the driveway at 3 a.m,” J.C. Collins, a marketing executive at Ford, told Bradsher in High and Mighty.

But automakers spent huge amounts of money generating demand for their profitable new gas-guzzlers. Auto advertisements at the time featured SUVs crawling over rocky mountain roads and hauling trailers.

SUV advertising grew from $172.5 million in 1990 to $1.51 billion in 2000. That decade, automakers and dealers spent a combined $9 billion pushing SUVs on consumers, according to data gathered by Bradsher.

Obama and Biden missed opportunities to close the SUV loophole

There have been many opportunities to close the SUV loophole over the decades. But each time lawmakers attempt to do so, automakers prove that they are as powerful as they were a generation ago.

One of the best opportunities to close the loophole came in 2009 when Obama took office. Then, like the 1970s, gas prices were sky-high. Then, like the 1970s, a new environmental movement was emerging, this time focused on climate change. But when the Obama administration redesigned fuel economy standards they left the loophole open.

Since Obama’s fuel economy standards were announced in 2009, the share of SUVs has doubled from about 25% to 50%.

In 2021 another opportunity to close the loophole emerged when the Biden administration designed their fuel economy standards. But once again, regulators failed to close the loophole. Instead they designed standards that allowed trucks and SUVs to put 41% more CO2 into the atmosphere than sedans offering automakers an incentive to produce bigger cars and skirt regulation.

It’s tempting to think that none of this really matters going forward. After all, many of the world’s biggest automakers have announced plans to electrify their vehicles over the coming decades. EVs, unlike gas-combustion vehicles, don’t emit CO2 out of their tailpipes regardless of their size.

But to ignore the SUV loophole and the problem of oversized vehicles would be a major mistake even in the age of electrification. That’s the argument I’ll make in the next installment of this story.

I assume the "footprint" rule will be covered in part 2.

One other characteristic did push folks to SUVs from cars, vans and a few ol' wagons. The latter's ground clearance was lowered as any easy way to get mpg and handling improvements. FWD cars which were initially good in snow became less so as rear weight increased with safety improvements. Many folks gave up on "cars" because they scraped off their mufflers and air dams and hung up on snowy berms or even speed bumps. No, most folks don't take SUVs "offroad," but that's not really the important distinction. It's Uncle Bob's driveway or the occasional two-track to a trailhead or the cobble in middle of the state highway. Or, being from low-gas-tax Colorado, the wheel-eating potholes.

But we did survive with smaller, lighter vehicles before the Expedition MAX and 4dr 4wd luxury pickups were everywhere, inspired by lame regulations and lame corporations.

Having said that, neighbors get real world 35 mpg in Rav4 true hybrids and even 33 mpg in the Highlander hybrid which is ginormous to me, so our mpg stds could go way up. My rides are one of the Fiat Jeeps, with typical crappy mpg but available as PHEV in the EU last I checked, and a little Kia PHEV with too short battery range. I covet the Rav4 PHEV, though of course it has some annoying lower air dam in front. Long (i.e. 40-60 mi) battery-range PHEVs would sell here and be in EV mode most of the time. BYD is cranking them out for the Chinese. So yeah, we need to stop compromising on lame standards and rules and regs that engender all kinds of teeth-gnashing and then don't really get the job (GHG reductions) done. Whew!

What does it mean for batteries, road and parking concrete weight, EV dispersion, to stay under 1.5 deg by 2030?