The Man Trying to Kill America's Offshore Wind Industry

He's fighting every offshore wind project in the country and recruiting hundreds to join him. Here's how.

In the fall of 2019, residents on the coast of New Jersey, Delaware and Maryland started to receive letters about a new offshore wind project from what appeared to be a neighborhood group, Save Our Beach View.

The project, Skipjack Wind, promised to provide enough clean electricity to power 40,000 homes. The developer planned to invest $225 million into the local economy and hire 1,400 people to build the turbines. At about 20 miles off the coast, it would hardly be visible to residents on even the clearest days.

But the letter didn’t include any of this information. It began: “If you are like me, you come to the beach to relax, enjoy nature, and life in a shore community. Most are not aware that this is about to be changed forever.”

The letter falsely claimed that the project could cause coastal residents’ property values to drop by between 20% and 30%; power costs could rise by 400%; key industries like tourism could see their revenues fall by 50%.

Over the course of a few months, 35,000 homeowners received this letter. Many of these residents would eventually be targeted with Facebook ads, aerial banners flying above the beach, and op-eds in their local paper. While the medium of communication varied, the message was always the same: for coastal residents, Skipjack Wind would ruin life as they knew it.

What few of these residents knew was that this was a part of a nationwide effort to kill the offshore wind industry, orchestrated by a conservative think tank. Still fewer knew that one of the think tank’s biggest donors was a fossil fuel industry trade group that counts ExxonMobil, Chevron, and Marathon Oil executives as part of their board.

Today the campaign poses one of the biggest threats to America’s offshore wind industry.

How a conservative think tank created a fake resident group

The mastermind behind the letter campaign was David Stevenson, a director at the Caesar Rodney Institute. For more than a decade Stevenson has worked for the conservative think tank to advance the interests of the fossil fuel industry and fight environmental regulation. In 2018, Stevenson set his sights on the nascent offshore wind industry. But rather than use his usual methods of political advocacy, he decided to change things up a bit.

In his past efforts to fight electric vehicle rebate programs and carbon pollution regulations, Stevenson did what most conservative think tank employees do. He produced dense reports packed with data. Then he sent them through his network where they eventually landed on the desk of sympathetic legislators and regulators.

But by 2018, it was well-known that Caesar Rodney Institute, was a small part of a nationwide political machine funded by the fossil fuel industry. Stevenson knew that in the work of political advocacy, who delivers a message is just as important as the contents of the message itself. In that respect, he had a problem. One of the think tank's biggest donors was the American Fuel and Petrochemical Manufacturers, a trade group that counts executives at ExxonMobil, Chevron and Marathon Oil as members of their board. It’d be too easy for opponents to dismiss his advocacy as the work of industry.

Stevenson solved this problem by creating a front group, Save Our Beach View, which appeared to be a grassroots nonprofit organized by coastal residents.

It was for this reason that when he sent his letter to 35,000 coastal residents, he didn’t sign it with his name or that of his employer, but instead as “a fellow concerned Delaware beach homeowner.”

The campaign was remarkably effective. In the letter, Stevenson asked residents to do three things: join the grassroots group, donate, and contact local lawmakers. 700 residents responded or signed up for more information on the website. 400 of those residents sent a combined $50,000 in donations to support the opposition effort.

In particular, Stevenson asked residents to oppose the construction of a nearby substation, a critical piece of infrastructure that would bring power from the turbines at sea to the electric grid on land. Hundreds of residents called their mayors, state senators, and other representatives. Within six months, the project developer withdrew their plans to build the substation due to the intense local opposition.

With financial support from the fossil fuel industry, Stevenson had successfully engineered that all powerful force in American politics: the local neighborhood group, driven by emotion and dedicated to defending the status quo.

But the Skipjack Wind project was just one of many proposed offshore wind projects on the East Coast. In order to make a meaningful difference, Stevenson would have to expand his campaign. Over the next three years, he would do just that.

Expanding the campaign

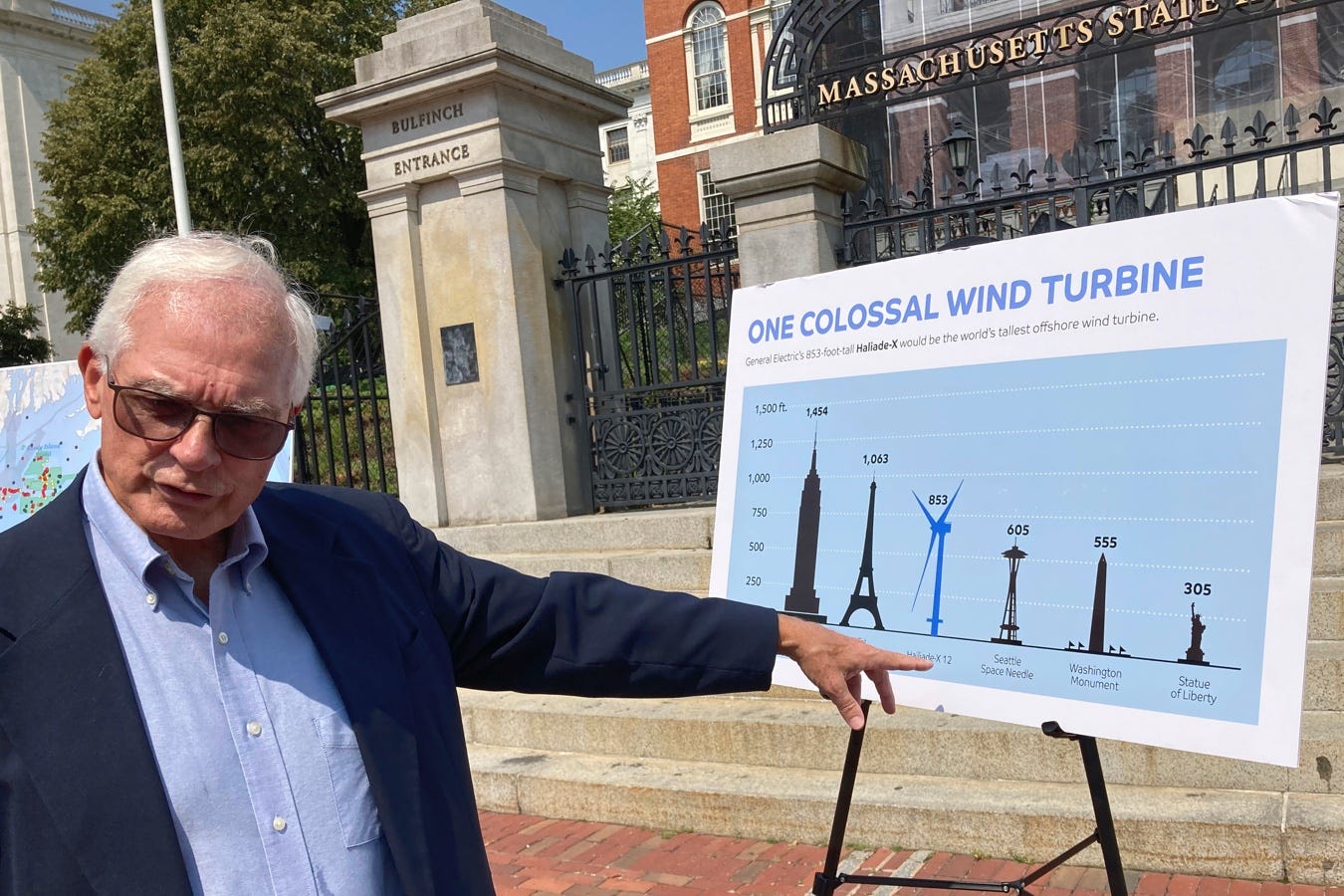

On a hot and humid day in August 2021, Stevenson showed up to the Massachusetts Statehouse dressed in a blue suit jacket, blue jeans, and blue tennis shoes. Standing alongside a group of residents from Nantucket, he announced to a small group of reporters the launch of the American Coalition for Ocean Protection (ACOP).

The new coalition would combine the emotional power of neighborhood groups like Nantucket Residents Against Turbines with the political expertise of conservative think tanks like Caesar Rodney Institute. With organizations in every coastal state from North Carolina to Maine, the coalition planned to sue more than a half dozen offshore wind projects in an attempt at delaying or killing them entirely. They also planned to use the lawsuits as an opportunity to raise the salience of their concerns to the broader public.

At the press conference, Stevenson announced that Caesar Rodney Institute had set up a $75,000 legal fund to support residents who wanted to sue offshore wind projects. He planned to raise a total of $500,000 for the campaign. According to the ACOP website, “The overall objective of the Fund and other ACOP activities is to at least create a permanent offshore wind exclusion zone to 33 miles off the entire eastern seaboard of the United States.”

Over the next year, Stevenson helped resident groups in the coalition flood the federal government with lawsuits.

Residents in Nantucket launched a lawsuit, claiming that the construction of a wind project off the coast of Massachusetts posed a threat to the critically endangered North Atlantic Right Whale. The lawsuit brought up legitimate concerns. According to the World Wildlife Fund, right whales are “one of the most endangered of all large whales,” due to commercial whaling operations that pushed them to the brink of extinction in the 19th century. Today, these whales are threatened by rope entanglements and vessel strikes. The group argued that construction of the offshore wind turbines would result in more risk to the endangered species.

But the right whale has been threatened by the fishing and shipping industry for decades. The Nantucket residents only began their advocacy when the developer announced the offshore wind project. When a Cape Cod Times reporter interviewed ocean scientists and whale advocates in January 2022, none of them had heard of the Nantucket group.

In June 2022, National Wildlife Federation, the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Conservation Law Foundation signed an agreement to support an offshore wind project off the coast of New York, so long as the developers engage in protective measures for the whales. The environmental groups believe the biggest threat to the right whale over the long run is climate change.

“Development of renewable energy resources is vitally important to the health of the planet, and it's vitally important to addressing climate change,” Conservation Law Center’s Priscilla Brooks told me.

In January 2022, residents in New Jersey sued the federal government claiming that a nearby offshore project would destroy their local tourism industry. At the time, Reuters ran a story about the lawsuit highlighting the group’s concerns.

Bob Stern, president of Save Long Beach Island, told Reuters that they are concerned by the aesthetic impacts of the turbines, and potential lost tourism due to their interference with Long Beach Island's current unobstructed seascape. The group says tourism is the community's "economic lifeblood."

Researchers at the University of Rhode Island published a paper in 2019 analyzing the impacts of offshore wind farms on tourism. They used empirical data based on the United States’ only offshore wind farm off the coast of Block Island, Rhode Island. The researchers concluded that the wind farm resulted in more tourism, not less. This study isn’t mentioned in the Reuters story.

By the end of 2022, the federal government faced lawsuits from resident groups in every coastal state from Maine to North Carolina. Many of the groups behind the lawsuits, like Nantucket Residents Against Turbines, received money from Caesar Rodney Institute’s legal fund and used the same law firm, Gatzke Dillon & Ballance. But this story has gone largely untold. CBS, Reuters, and AP News have all covered the resident groups in the coalition. None of them have mentioned who is funding their lawsuits.

Local newspapers have also failed to make the connection for readers. One of the resident groups in the coalition is Protect Our Coast. The donation button on their website takes visitors to a Caesar Rodney Paypal account. Local media outlets have covered Protect Our Coast 11 times, but none of them mentioned Caesar Rodney Institute or its donors.

In addition to misleading readers, this coverage funnels more residents to the resident groups’ websites and Facebook pages where they share misinformation about the projects.

Time is on their side

It’s still unclear whether or not Stevenson and Caesar Rodney Institute’s donors will be successful in their ultimate goal of stopping the projects. But unlike the developers, or those who want to see America transition to cleaner energy sources, time is on their side. Every day the project is delayed, power companies burn fossil fuels like natural gas and coal instead of the wind farm’s clean electricity.

Time also creates political risk. Skipjack Wind, the project Stevenson first targeted in 2018, was initially supposed to be completed in November 2022. After the substation was blocked, the developer was left scrambling to find another place to bring the power to land. Two years later, they are still trying to find an alternative site.

The developer hopes to complete the offshore wind farm in 2026. By then, a different president might be in charge of the federal agencies that can approve or revoke the permits needed to finish the project.

Want to support independent climate journalism?

For the last few months, I’ve spent hundreds of hours reporting on the fossil fuel industry’s efforts to slow down the transition to clean energy. For each story, I’ve read through public documents, interviewed experts, and distilled everything down into a series of short articles.

If you’d like to support my reporting, consider signing up for a paid subscription by clicking the button below. For $5 per month, you can help make these stories possible.

Since you (and others) blew the curtain away on CRI and its front groups, they've gotten smart(er) at trying to cover their tracks. For instance, the "donate" button on NJ's "Protect Our Coast" no longer directs to CRI. CRI and POC claim to be independent of each other. CRI claims that they only get "a little" money from the oil and gas industry. See WaPo https://www.washingtonpost.com/climate-environment/2023/08/08/offshore-wind-energy-east-coast/ Meanwhile, it seems to me that the anti-wind people are way more passionate about their position than the pro-winds. The antis, including the commercial fishing industry, are putting a lot of effort into flooding the zone with lots of claims against offshore wind and people seem to be buying it. Example: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BwfJJfG9vfo I have yet to see anything remotely equivalent on the pro-wind side.