These Data Centers Are Getting Really, Really Big

Gigawatt-sized data centers are becoming the new normal

A quick note: At my company, Cleanview, we recently built a data center tracker. I’ve been following the development of AI and data centers closely for much of the last few years. And even I’ve been shocked by what I’ve learned in building this product. Today I’m publishing the first story that uses our data center tracker. If you want to use the platform, you can sign up for Cleanview here.

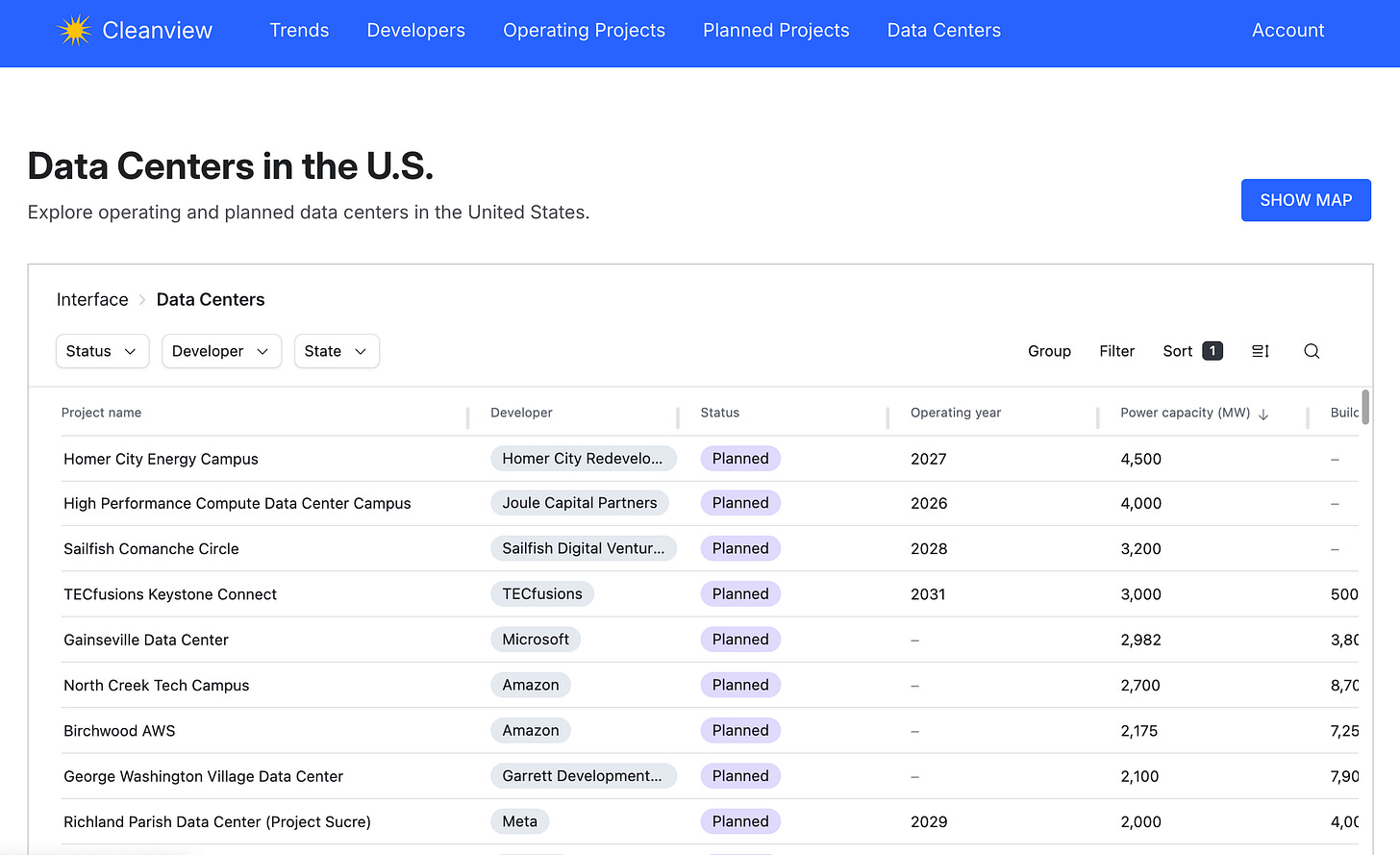

Update: We just released a free data center project explorer. You can use it to see data centers in the United States and in every state (e.g. Virginia, Texas, Georgia, etc).

There’s been a lot written about AI investment and its impacts in the last year. But somehow, I think most people still underestimate the scale of the current data center build-out that’s happening across the United States.

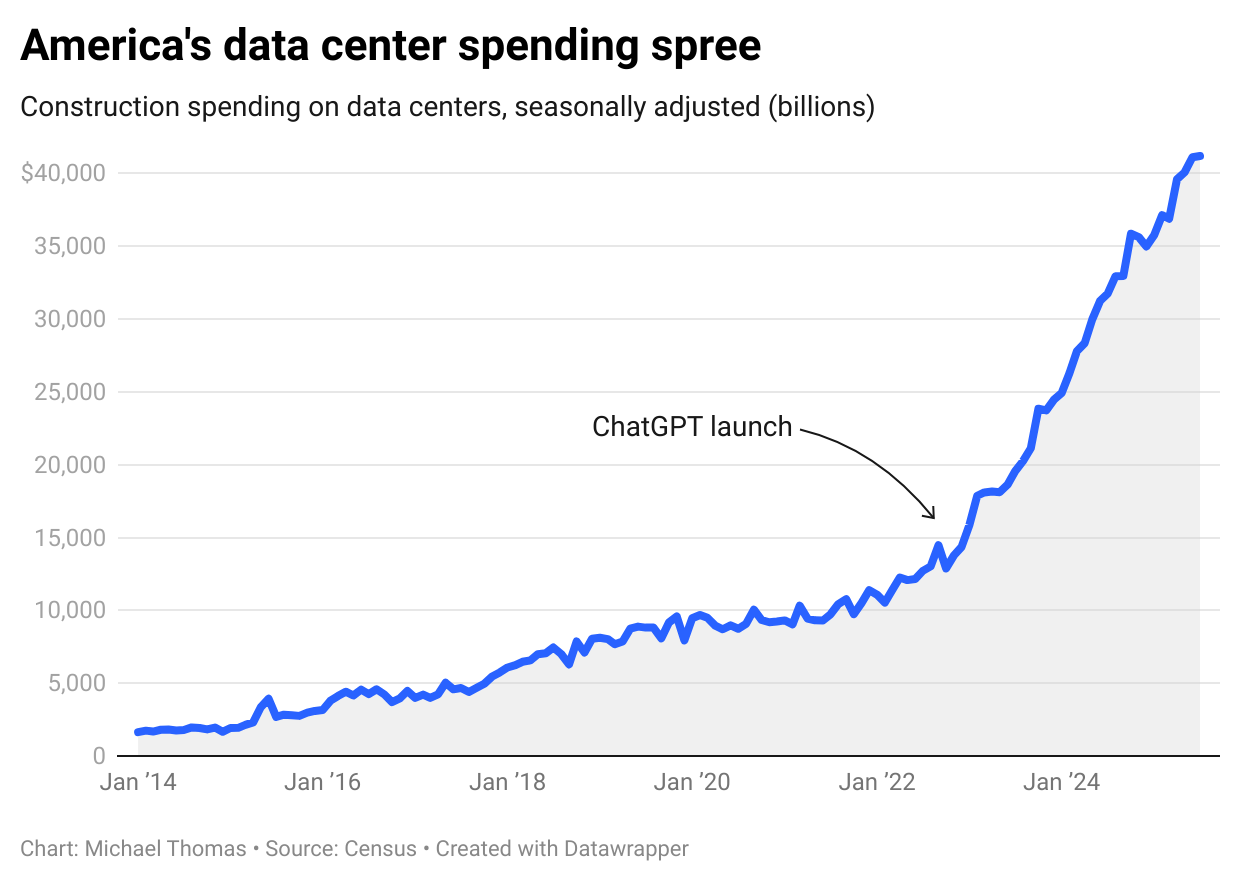

Since the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022, tech companies have spent huge sums of money building data centers. In just three years, spending on data centers in the US has gone from $13.8 billion to $41.2 billion per year—an increase of 200%. This has come at a time when virtually all other construction activity in the country has slowed.

I’ve been skeptical of the AI power demand story at times. But in the years since I first started writing about it, many AI infrastructure projects have gone from the realm of press releases to actual operating projects. And they’ve done it at breakneck speed.

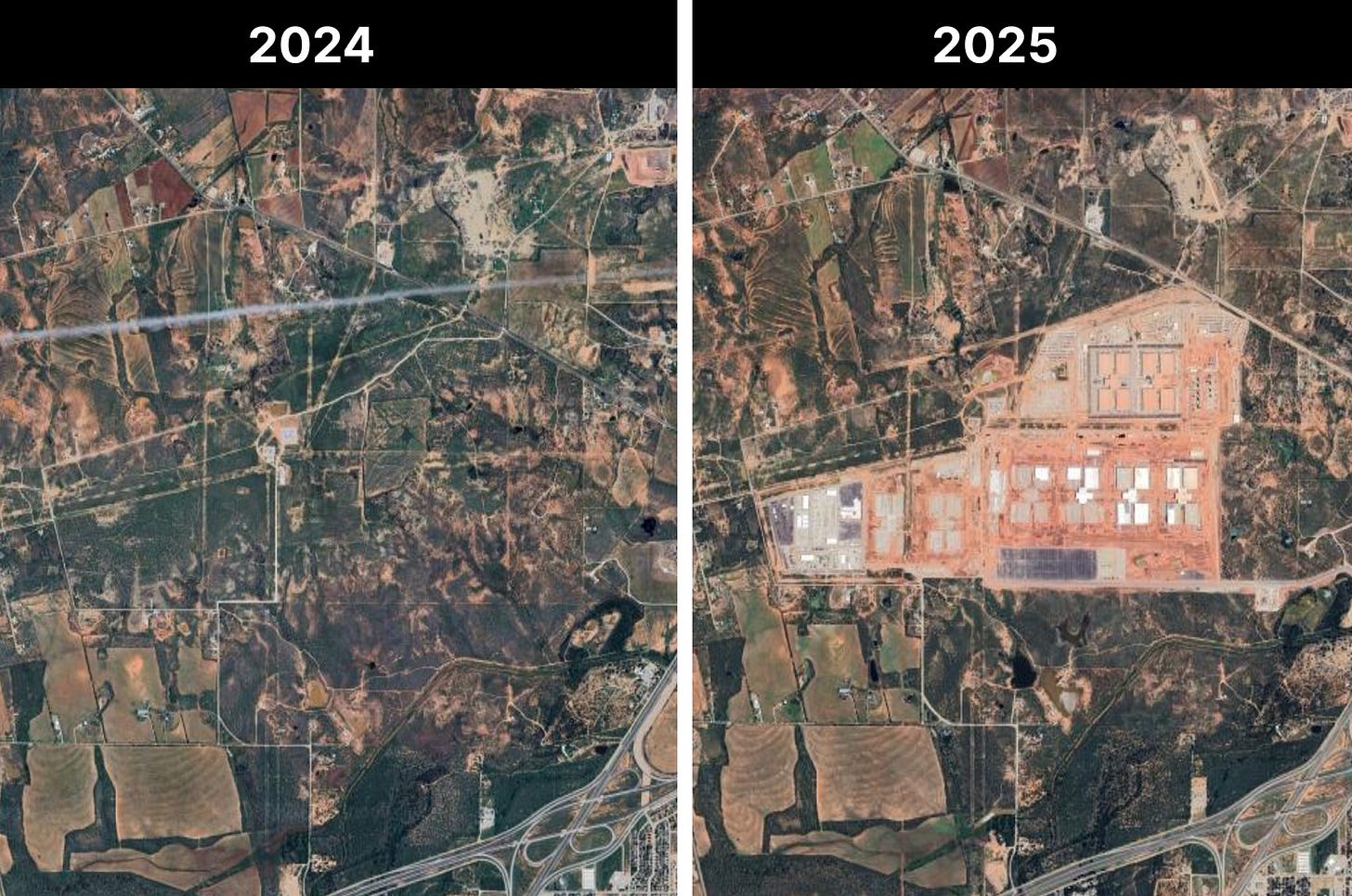

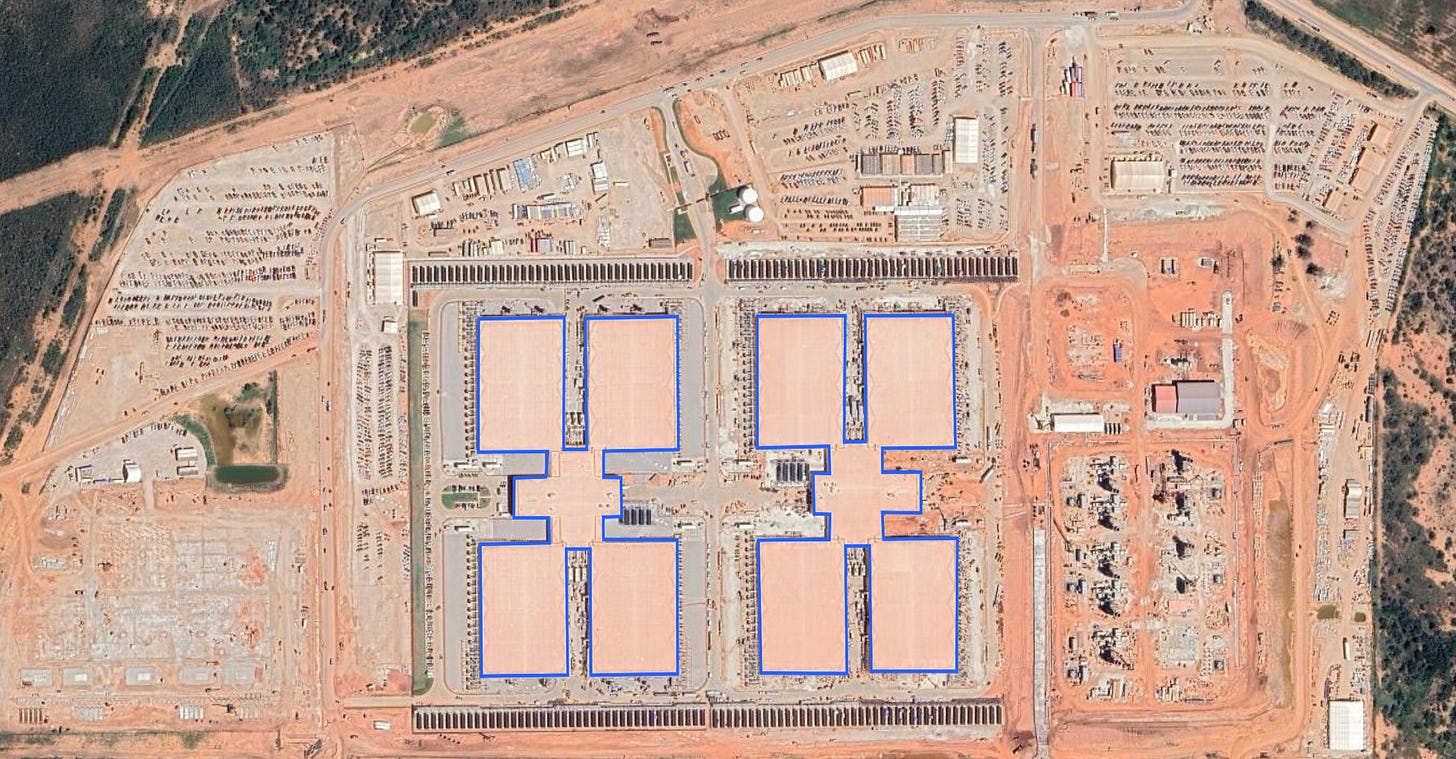

OpenAI’s Stargate data center in Abilene, Texas is one such project. Just over a year ago, the project’s developer had nothing more than some permits and a few hundred acres of dirt in West Texas. Today there are 100,000 of NVIDIA’s most advanced chips consuming 200 MW of power in the project’s first two buildings.

Over the next year, the developer plans to build another 6 buildings, bringing the site’s total power consumption to 1.2 GW.

It’s hard to really put the scale of this project in perspective. One way to do it is to look at the project from space. The satellite image below shows Stargate’s first two buildings. Each of those tiny little dots in the top left and top right are construction workers’ cars. There are about 6,000 of them shuttling workers to the site each day.

Another way to understand the scale of the project is to compare the 1.2 GW of peak demand the facility will use to that of one of the nearest utilities. El Paso Electric, a utility that serves 465,000 customers west of the project, has a peak system load of 2.4 GW.

Stargate isn’t the only gigawatt-scale project progressing quickly in the US either.

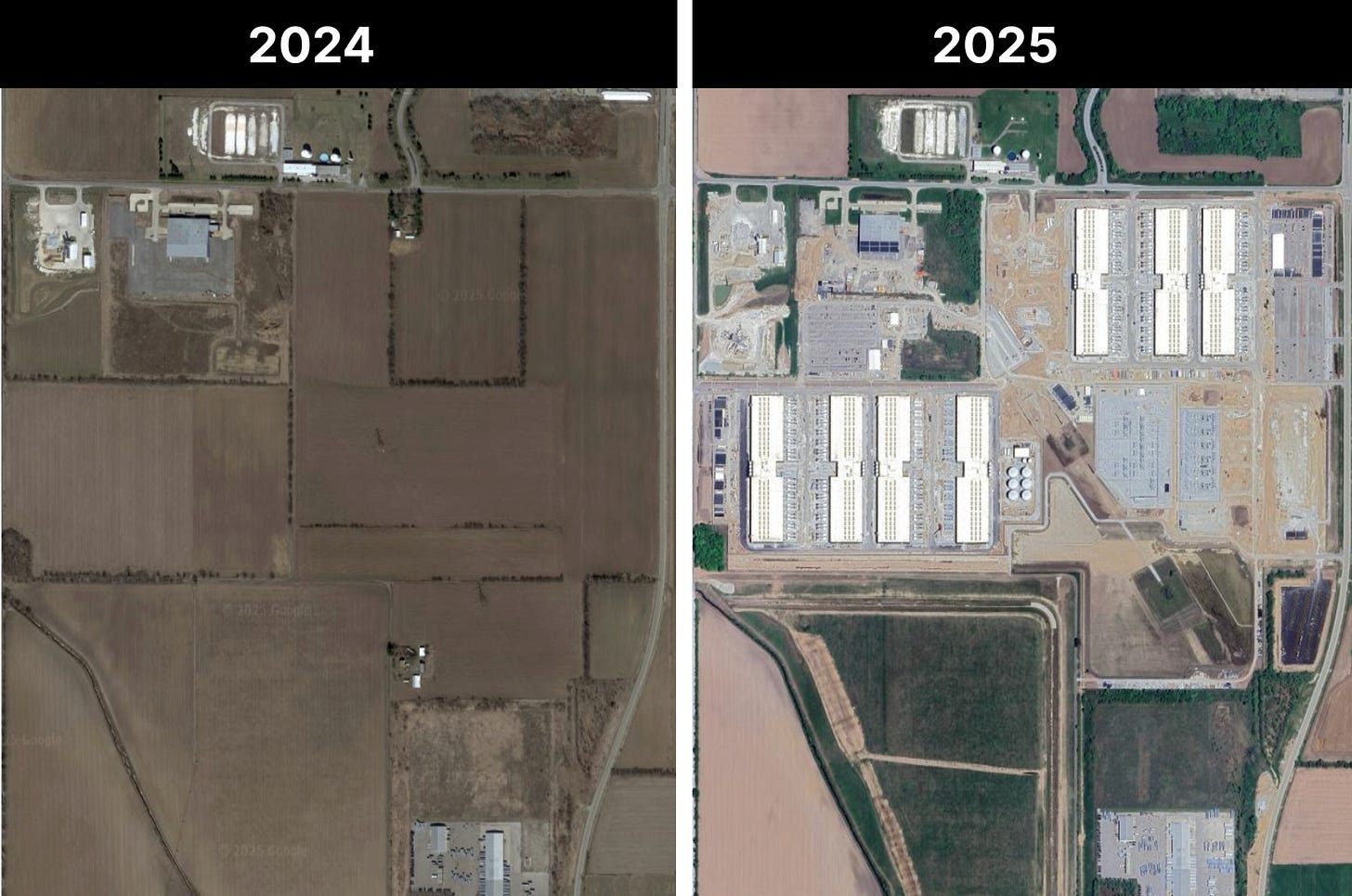

This summer, Amazon launched the first phase of its own mega-data center in Indiana—claiming to be the world’s largest for now. The company says it has reserved all of the power for its partner Anthropic to train the Claude model.

Amazon’s new data center in Indiana went up as quickly as Stargate. In early 2024, the site was nothing more than corn and soybean farms. Today, the first seven buildings are consuming about 525 MW of power.

Over time Amazon plans to build 23 more buildings, bringing the total power consumption to 2.2 GW. Each year, the single supercomputing cluster could consume as much electricity as half of all homes in Indiana, according to one estimate. When the site’s 30 buildings are complete, the total 6.9 million square feet of floorspace will be two and a half times larger than that of the Empire State building.

Microsoft recently announced the first phase of a giga-scale data center in Wisconsin. The site will eventually consume about 1.5 GW of power, according to documents from the region’s grid operator MISO.

Across its global footprint, Microsoft built 2 GW of data centers over the last year. Still, the company’s executives say it hasn’t been enough. In investor earnings calls, they’ve said that they have had to turn away customers due to a lack of power capacity.

For years, Google has been building a cluster of closely connected data centers on the border of Nebraska and Iowa. A collection of four different sites within 100 miles of each other will soon have about 1 GW of power between them all, which will be used to train the company’s Gemini model.

Elon Musk’s xAI famously dodged environmental regulations when the company brought in mobile natural gas generators to build the first phase of a gigawatt-scale data center in Tennessee. When regulators caught wind of the move progress at the project and permit approvals for the second building slowed. So Musk bought a power plant just over the border in Mississippi where regulators said they’d delay enforcement of air pollution laws for a year. The second phase of the project could consume as much as 1.5 GW of power.

But for each tech giant none of this is happening fast enough.

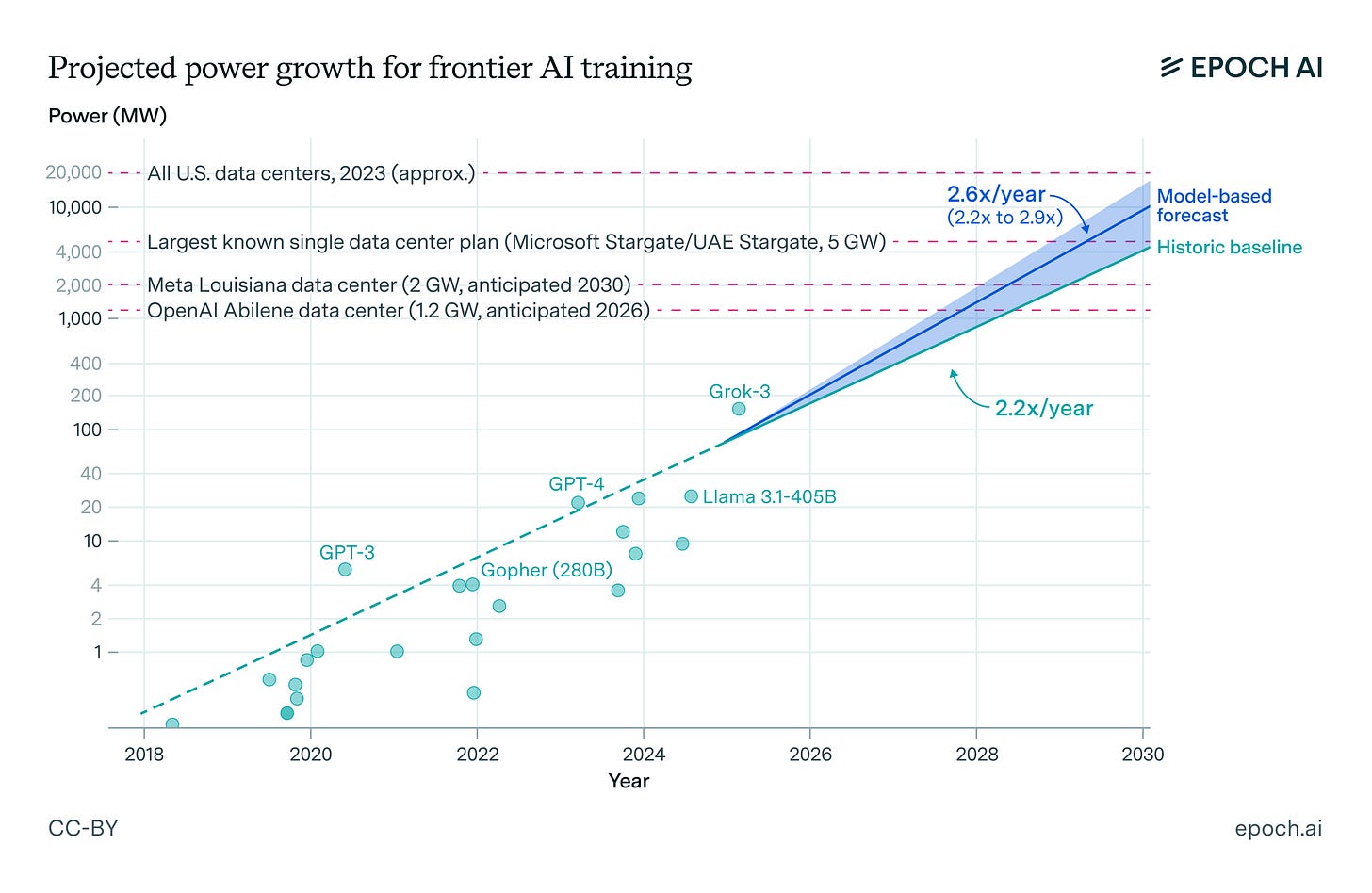

In the current era of AI, the quality of a model is determined primarily by compute and power. These so-called “scaling laws” are the reason why NVIDIA went from being a relatively unknown gaming chip maker to the world’s most valuable company in record time. Throw more chips and power at your model, and it performs better on benchmark tests.

When tech CEOs are at fancy dinners with the President or give TV interviews, they tend to talk about all this as a race against China. But they’re really all in a race with each other to build the best model so that everyone switches over to it and their stock price goes up.

The problem is that this race to become the first $5 trillion company requires physical infrastructure, and building stuff in the real world takes a long time. Even more challenging, scaling laws are logarithmic: each meaningful step forward, in terms of model quality, requires 10x more compute and power.

ChatGPT 3 was trained with less than 10 MW of power. Grok 3, the most advanced model released this year—as measured by the industry’s favored benchmarks—used 100 MW. OpenAI, with its Stargate project mentioned above, is aiming for a 1,000 MW training run soon.

This has led to some pretty strange ideas when it comes to building data centers.

Mark Zuckerberg recently ditched the data center designs that Meta had perfected over the last decade and told his team to stick tens of thousands of chips in tents outside their data center in New Albany, Ohio. Each of these chips costs about $60,000. Zuckerberg plans to stick billions of dollars worth of them in the tents.

That might sound crazy, but it’s cutting the time to build computing capacity in half. The first five buildings at Meta’s New Albany, Ohio data center took between two and three years to build. Meta started building five ~125,000 square foot tents between April and June, according to city permits. The company expects them to be complete within a year. Satellite images taken a month ago show that all five structures have already been built.

Zuckerberg recently took to his platform Threads to say that the data center, which the company has dubbed “Prometheus,” will be the largest in the world by the time they’re done setting up camp.

Electric utilities that serve these data centers are struggling to keep up. Between permits, interconnection studies, and construction, a typical solar, wind, or battery project takes about five years. The current backlog to buy a gas turbine stretches into the early 2030s. Transmission line projects take about a decade.

The gap in how long it takes to build data centers—or in some cases, GPU tents—and how long it takes to build power infrastructure is one reason why the utility, AEP Ohio, was forced to pause all data center interconnections recently.

That pause threatened the growth of Meta’s Prometheus project. So again, the company came up with a workaround, this time by eschewing the grid entirely. The company recently received approval to build a 400 MW natural gas power plant next to its tents. Shortly afterwards, the company increased the planned capacity of its onsite power plant to 700 MW.

Prometheus could be the largest data center in the world next year. But Meta hopes that won’t be the case for long.

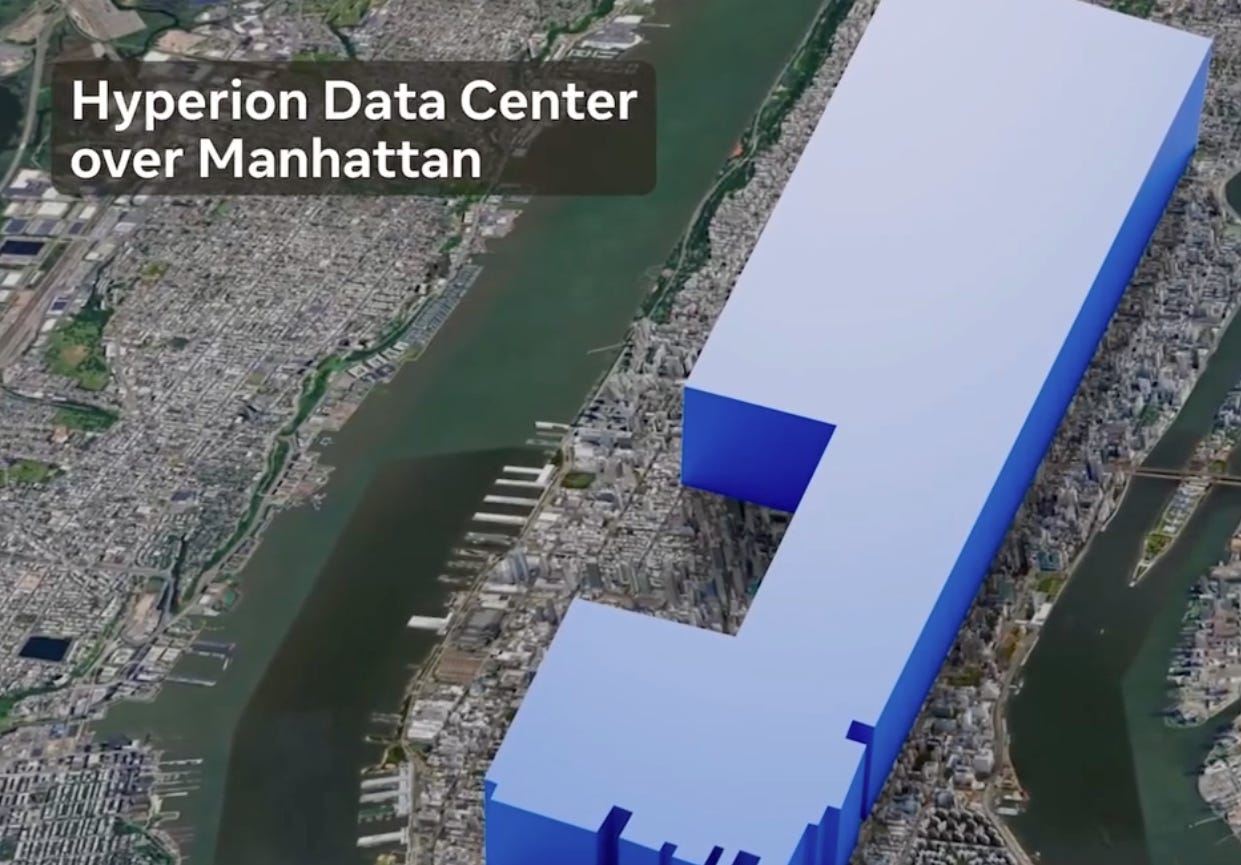

In Louisiana, Meta is building a data center, called Hyperion, that will be twice as large as its Ohio data center. The floorspace will be about half the size of lower Manhattan.

At peak power, Hyperion will consume about half as much electricity as the entire city of New York. The project will be powered by a 2 GW combined-cycle gas plant.

Meta will pay for $3.2 billion of the gas plant and associated transmission infrastructure’s cost. Louisiana residents and businesses will have to pay $550 million of the project’s cost.

The trillion dollar question

How long the current data center build-out will continue is one of the most debated questions in America right now.

In the last month alone, OpenAI announced deals with chipmakers to deploy 26 GW of power-hungry GPUs. Those chips and the infrastructure required to house them would require more than a trillion dollars of investment. The company’s CEO, Sam Altman, has told investors that he wants to deploy 250 GW of computing capacity by 2032.

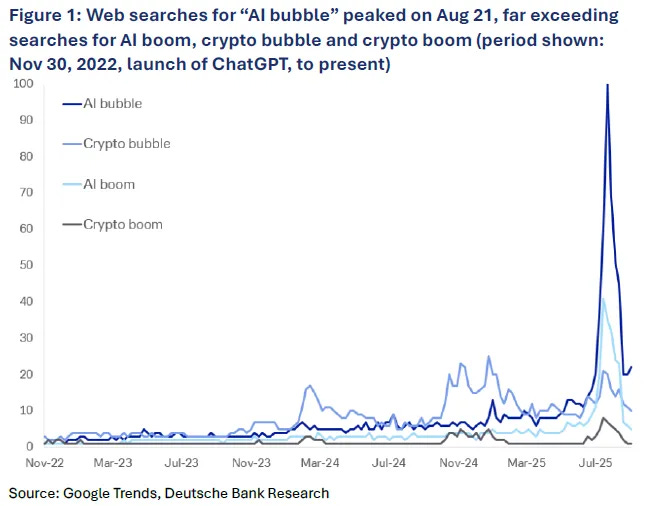

Absurd numbers like this have led just about everyone to suggest we might be in a massive AI bubble. Altman and OpenAI’s Chairman Bret Taylor have even said we’re probably in a bubble.

For anyone hoping that AI isn’t a bubble, the historical record looks bad—even if you assume the technology is transformational. As many have pointed out, railroads and the internet changed the world; they also wiped out investors and companies along the way producing two of the largest bubble’s in history.

But sensing that things feel frothy and calling the exact timing of a bubble’s peak are two different things entirely.

Alan Greenspan delivered his famous “irrational exuberance” speech warning that the stock market might be overvalued on December 5, 1996. That month, the Nasdaq index hit 1,000. It would take another 3.5 years for the index to peak at about 5,000 in March 2000.

The current wave of AI hype could grind to a halt soon. Companies may be slow to integrate large language models into their workflows. The scaling laws that recent progress has depended on—which are very much not laws—could stop working.

But there’s another possibility that I think everyone needs to be prepared for: a future in which these tech companies, with their huge and steady flows of profits, continue to invest aggressively for years to come. In that future the gigawatt-scale data centers of 2025 might even look modest.

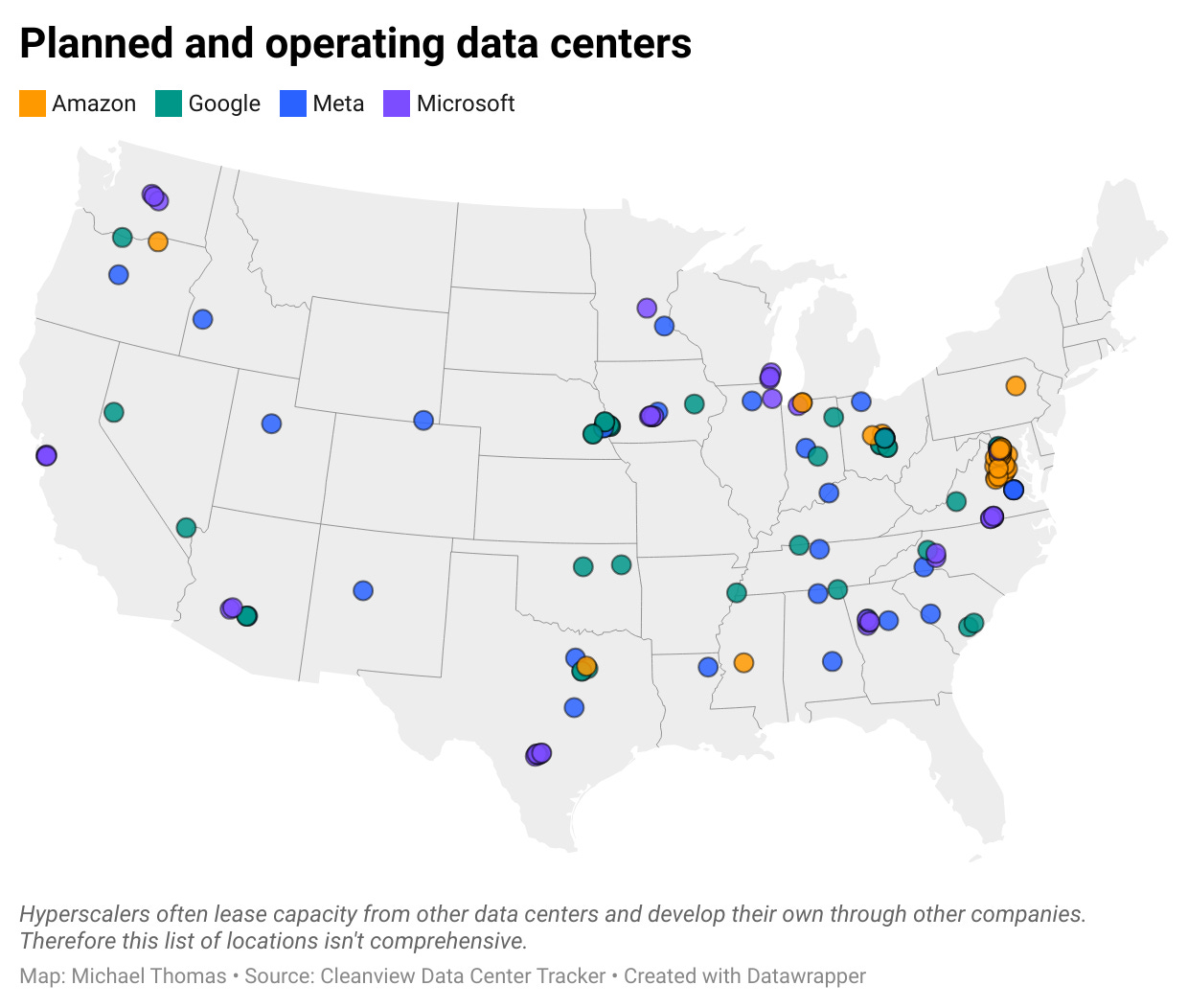

Cleanview’s new data center tracker

To write this story, I relied on Cleanview’s new data center tracker. Our team spent months going through public records, reviewing satellite images, and scouring the web to build one of the most comprehensive datasets of planned data centers in the US. We’re tracking about 550 planned data centers with a combined power capacity of 125 GW. Each week we track newly proposed projects, permitting updates, and cancellations.

If your company or nonprofit is interested in using the platform, you can try it out for free for 7 days by clicking the button below.

To your point, Michael – a simple “data center” search in Halcyon Search shows 13,708 filings, dockets, and regulatory documents mentioning data centers in 2024 alone.

For 2025, we’ve already surpassed that with 13,985 – and we’re only in October!

This article comes at the perfect time. I completely agree, the scale of this data center build-out is truly astonishing. It makes you wonder how quickly the infrastructure can even keep up. Great insigts.