Can a Story Change Someone's Mind?

A new study and a few reflections on my first three years writing this newsletter

A few weeks ago, a researcher at Northwestern University sent me a message. He and his coauthors had just published a study that aimed to answer a question I think about a lot: Can a story change someone’s mind?

As a writer I’m predisposed to think the answer is yes. To believe the alternative is to admit that everything I do is basically useless.

But there was another reason the study caught my attention: To run the experiment, the researchers took an adapted version of one of my most popular stories—a case study of how Paris made their streets more bike- and pedestrian-friendly and transformed the city in the process—and showed it to 400 Americans.

The researchers wanted to know if showing Americans examples of how other countries have built more sustainable cities would make them more likely to support urban transformations in their own communities. In other words: can a story bike-pill a nation of SUV drivers?

What they found was more encouraging than I would have guessed. Here are some of the results:

People who read the story were more likely to support policies like bike lanes and pedestrian zones.

They were more willing to reduce their own car use or say they’d vote for sustainable transportation policies.

And they were more likely to want to read more about sustainable transportation.

Read the story they adapted or watch the video on the same topic.

These types of studies should always be taken with a grain of salt. The results might not hold when expanded to more than 400 people. If someone can change their mind so easily, that means the next Ford F-150 ad—which has millions in advertising dollars behind it—could theoretically swing them right back the other way. And the obvious one: study environments are not the real-world. It’s unclear how any of these people will actually vote in the next city, state, or federal election.

And yet, it proves, to a certain degree, the idea that has motivated me to write this newsletter for the last three years: Stories can change minds.

Reading this study made me reflect on why I started Distilled in the first place. In today’s newsletter I want share a bit of backstory on how I got started.

Why I started Distilled

I first started thinking about this newsletter in the summer of 2022. I had just donated all the assets of my company, Carbon Switch, to the nonprofit Rewiring America. And I was unsure what to do next.

That summer, my wife, son, and I took a month-long trip to Amsterdam. It was a radicalizing experience. I knew from other travel in my life that America was a uniquely car-centric, sprawling place, but to live in one of the most people-friendly cities in the world for a month, made me feel simultaneously inspired and angry. Why wasn’t my city designed like this?

When I returned from that trip, I started sketching out the first ideas for this newsletter. In my journal, I kept coming back to the same question: How could I recreate the experience I had in Amsterdam and show people in my country a different world that was possible?

Most humans are fundamentally conservative. As the authors of the paper I wrote about earlier put it, people “seek to avoid uncertainty, often prefer the status quo, and are not always aware of alternatives.”

This is a problem at a time that demands incredible change. To address the climate crisis, we need to radically alter our societies and the physical environments that surround us—and we need to do it in just a few decades.

In starting Distilled, one of my goals was to encourage some of that change by telling stories of the people who had already taken the first steps towards a more sustainable future.

Viral stories of progress

As anyone with an idea journal knows, it’s a lot easier to write about doing something than to actually do it. As soon as I tried turning my fuzzy ideas into something real, I was hit with an overwhelming number of questions and doubts. What form should the thing take? Did the world really need more “stories to inspire change”? How would I ever make enough money doing this to make a living, let alone pay for my son’s $25,000 per year daycare?

For a few weeks, I did nothing with my idea. I showed up to my office each day and rather than produce stories, I consumed them. I read articles, books, and surfed the internet, telling myself that I was doing “research.” Deep down, I knew that all of this was just a way of delaying the hard work of writing and of putting my ideas out in the world. I knew that I was choosing safety over discomfort. And yet, I didn’t know where to start.

Finally after weeks of delay and procrastination, I decided to start with a tweet—or rather a series of tweets.

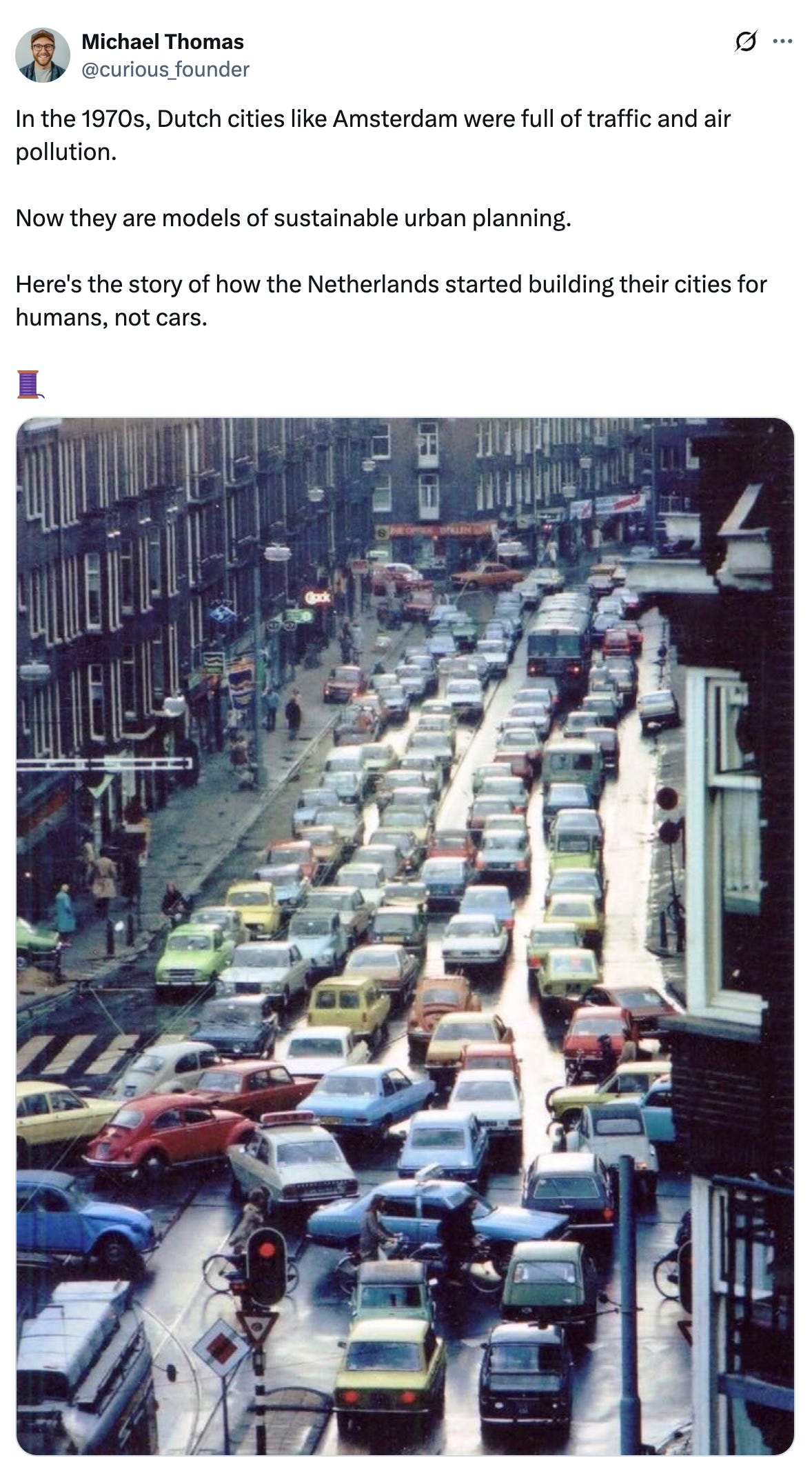

One afternoon, just before leaving the office, I posted an image of Amsterdam in the 1970s and wrote a short history of how a group of activists transformed a car-centric, polluted city into the biking and public transit utopia most people know it as today. I posted the tweet, turned off my computer, and biked home. By the time I logged back online that night, it had been shared more than a thousand times. It would eventually be read by more than a million people.

Over the next month, I continued to post stories like this. I would spend a couple days researching a topic, write up a story, and cut a thousand words down into a few hundred. Then I’d create up to a dozen different versions of an image in search of the one that could best hook readers.

A part of me hated this creative process. Like many writers, I prided myself on the ability to write a 5,000 word magazine story. It’s in the depth of a story that nuance emerges, yet, in every act of distillation, I felt like I had to filter out important context. I wanted my ideas to reach people though and so I decided to meet people where they were as opposed to where I wanted them to be.

If reaching large audiences was the goal, that approach was a success. By the end of the first month, my stories racked up nearly five million views. Within a few months, I had turned that audience on social media into a growing newsletter audience that would soon have more than 15,000 readers.

I continued to try bring the stories to new audiences. Shortly after launching this newsletter, I started a YouTube channel. One of the first videos—an adaptation of my first Amsterdam story—reached more than 400,000 people.

Even as these stories reached millions of people, I doubted their impact. Each article, video, and social media post felt so small when compared to the scale of the climate crisis—of all the crises facing our world, for that matter. Our world needs action, not words and pictures, a voice in the back of my head told me.

Yet between these moments of doubt, came proof that stories do matter.

One entrepreneur who left his job at Google and eventually raised $33 million to build a better heat pump, told me that one of my stories encouraged him to start looking into heat pumps in the first place. A Congresswoman told me that my story encouraged her to launch an investigation into a company spreading disinformation online. Countless others reached out to tell me about the action they were taking in their homes and in their communities.

Shifting attention

I still have my doubts about the power of stories.

When I think about what is needed to curb emissions and adapt to a warming world, my first instinct is to rattle off a few recommendations: We need people to run for office that will pass bold climate policies and fight all the powerful interests standing in their way. We need people to invent new technologies and bring down the costs of climate solutions. We need literally billions of people to change their behavior—and to be open-minded to change around them—in ways big and small.

Nowhere on this list is anything to do with words or pictures. And it’s true: the stories we tell at the dinner table, like the cultural stories we tell ourselves as a society, can only do so much.

But my experience writing this newsletter has taught me that sometimes stories are the spark that shift our attention. Stories show us that another world is possible. And maybe most importantly, they can remind us that that world is worth fighting for.

To everyone who has read this newsletter over the years, and to those of you who have been generous enough to share your own stories with me and sent me kind emails, thank you.

As always, you can say hello, share what’s on your mind, or suggest story topics by responding to this email or commenting below.

- Michael

Hi Michael: I’m thinking of the old adage that “a picture is worth a thousand words”. So how can we find photos that tell a compelling story about how the “Big Beautiful Bill” could make everyday survival more difficult for the working poor who rely on federal assistance like SNAP and Medicaid benefits? How can we put a human face on these policy changes?

You mention a solution is making climate solutions less expensive but here is a related idea: making clear that climate solutions save money, here and now because they Multisolve, such as immediate health improvement and cost reductions. See Multisolving.org and book Multisolving by Elizabeth Sawin