Data Centers Are Pushing Arizona's Grid to a Breaking Point

Power demand is rising faster in Arizona than almost anywhere in the country

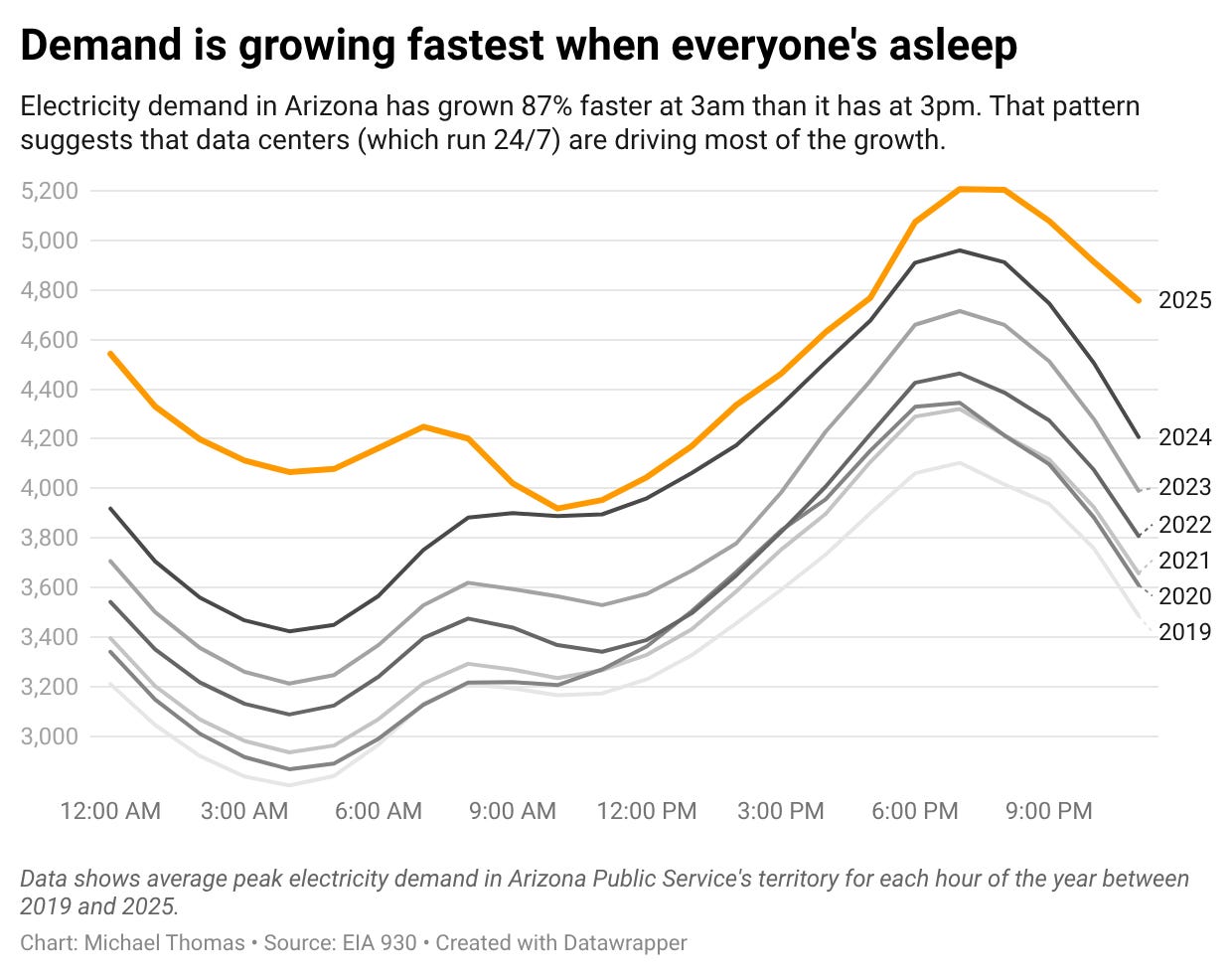

When night falls in the Arizona desert, millions of people retreat indoors, turn off the lights, and go to sleep. As the temperature drops, air conditioners cycle down. Office buildings go dark. Electricity demand drops—or at least, it used to.

At all hours of the night, in windowless buildings scattered across Phoenix’s sprawl, machines that never sleep now hum away, drawing power around the clock. Hundreds of miles of yellow fiber optic cables connect thousands of cabinets filled with these machines—each one serving up a video, ChatGPT query, or newsletter like this.

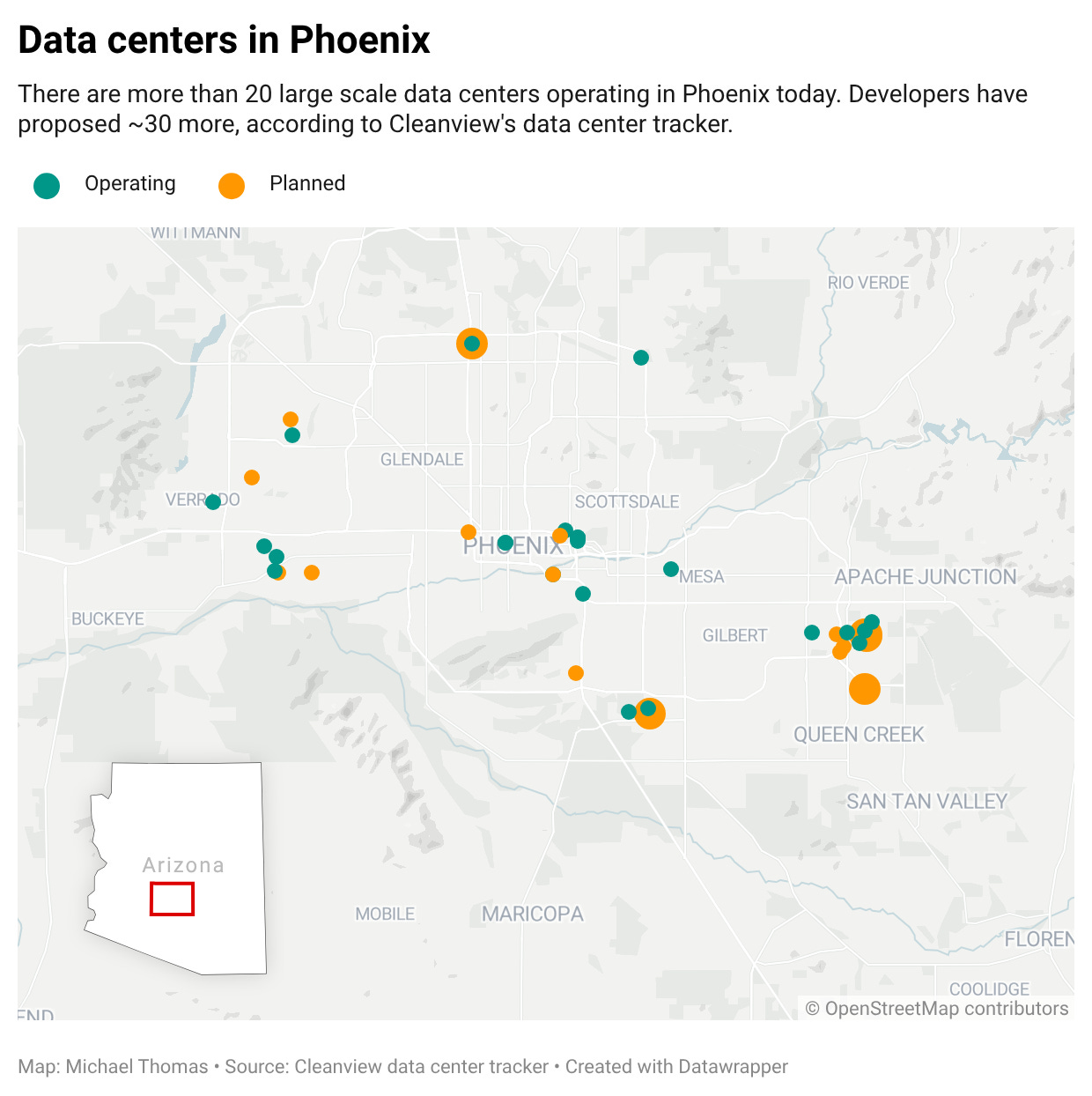

Few places in the world are seeing more demand from data centers than Phoenix. In the last few years, developers and tech companies have built more than a dozen large-scale data centers. The combined capacity of operating data centers in Arizona is now more than 2,000 MW, according to Cleanview’s data center tracker.

But that’s nothing compared to the growth that is likely to come over the next decade.

Arizona's three major utilities are grappling with data center interconnection requests that would dwarf their existing grids. Arizona Public Service (APS)—which currently peaks around 8,200 MW—has 30,000 MW of data center requests sitting in their queue.

"We've never sat in a position before where somebody's asking you to triple the size of your company," Jacob Tetlow, APS's Executive Vice President, recently told KTAR News. APS's average data center request now stands at 500 megawatts—enough to power roughly 375,000 homes.

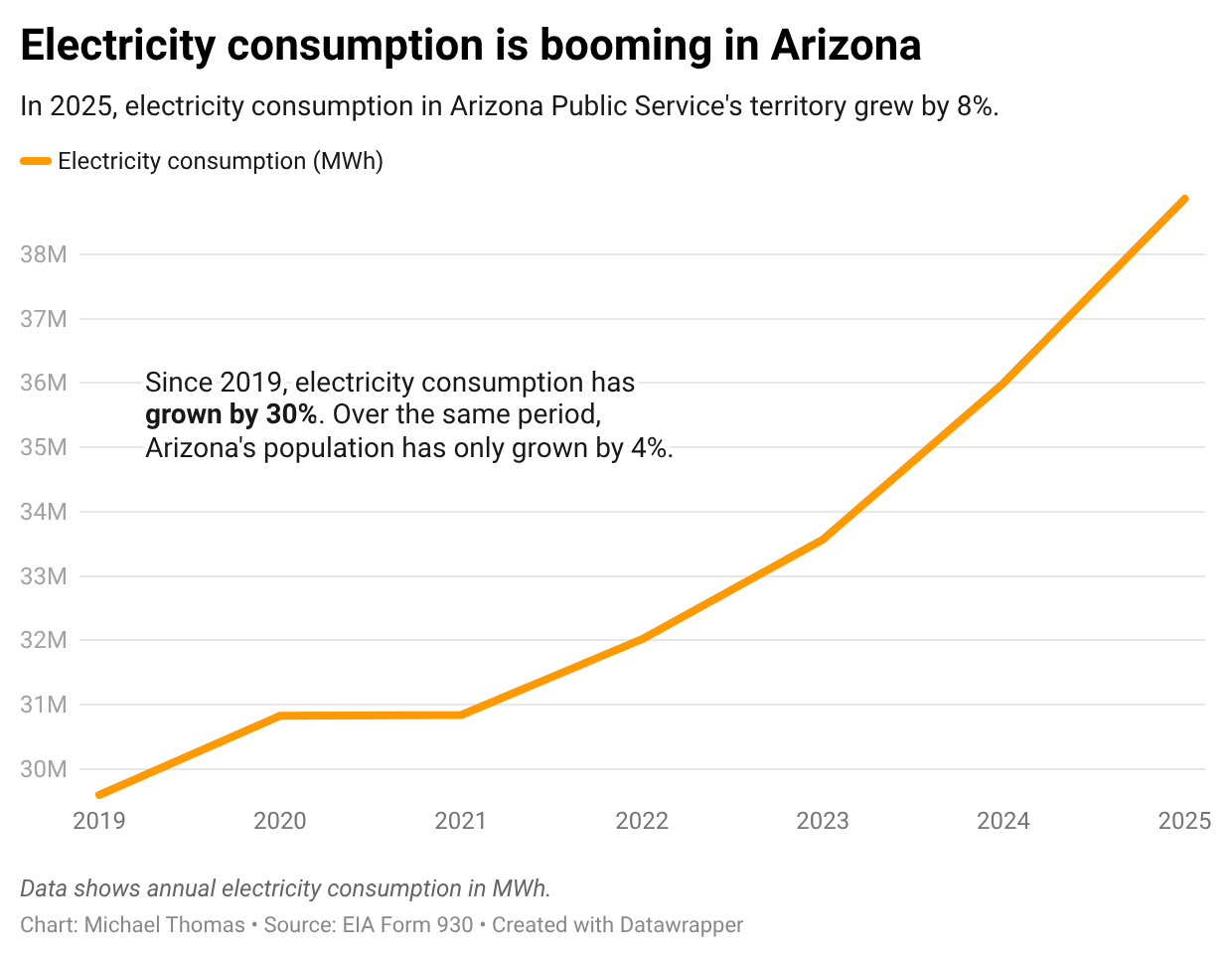

Already data centers are causing electricity demand to rise faster in Arizona than almost any other place in the country. In 2025, electricity demand in Arizona grew by 8%—a growth rate 4x larger than that of the United States as a whole.

Utilities have received so many requests from data center developers that they’ve had to start turning some away for fear of breaking the grid.

“The utility cannot commit to serving them because it would put existing customers at risk of having poor reliability,” Jose Esparza, APS Senior Vice President of Public Policy, told a NARUC conference in November 2024.

Utilities have found a way to accommodate many of the requests, however. Nighttime electricity demand—a good proxy for data center demand in Arizona—grew by 45% between 2019 and 2025.

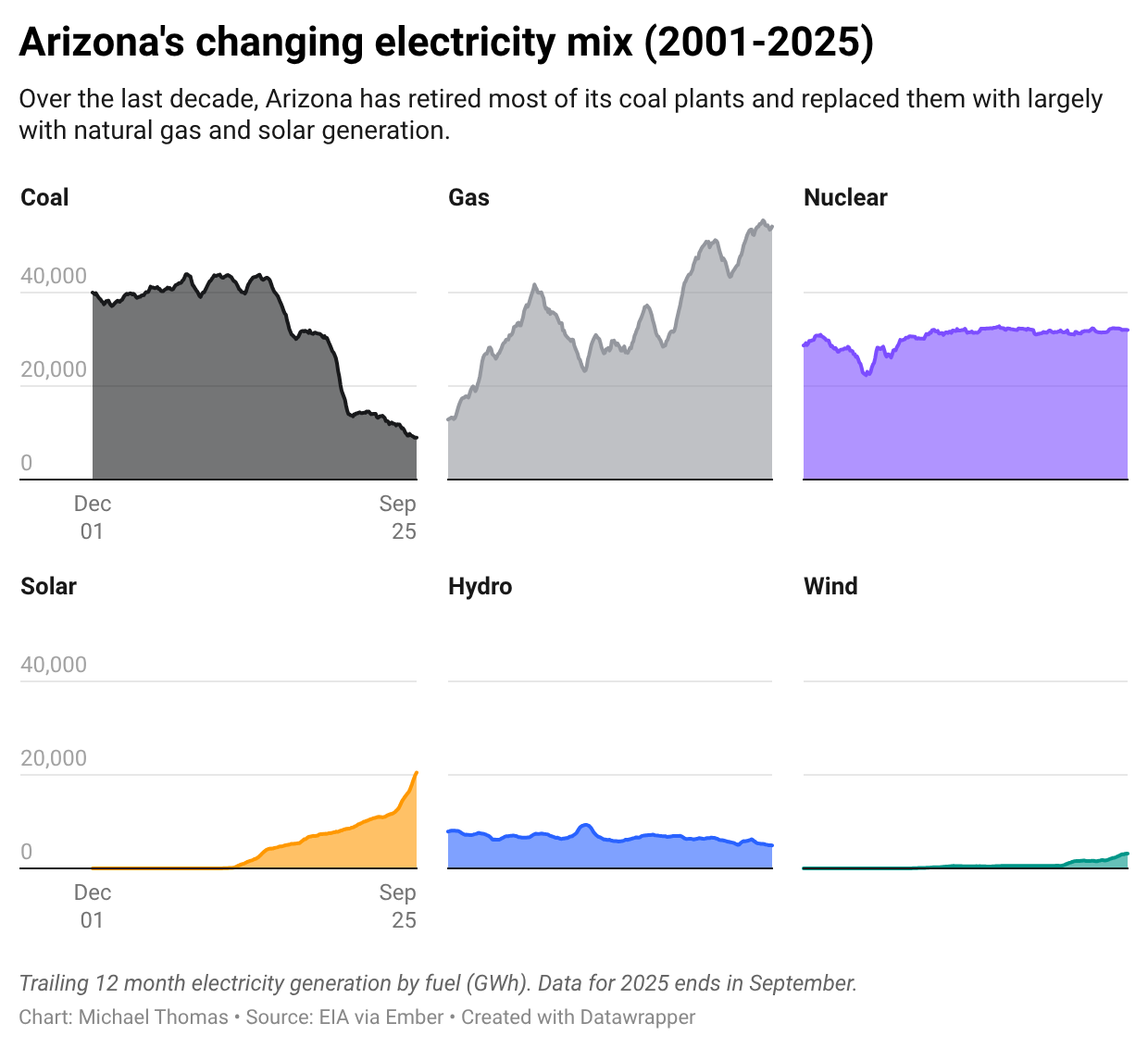

Data centers’ round-the-clock demand for power has made decarbonization in Arizona more difficult.

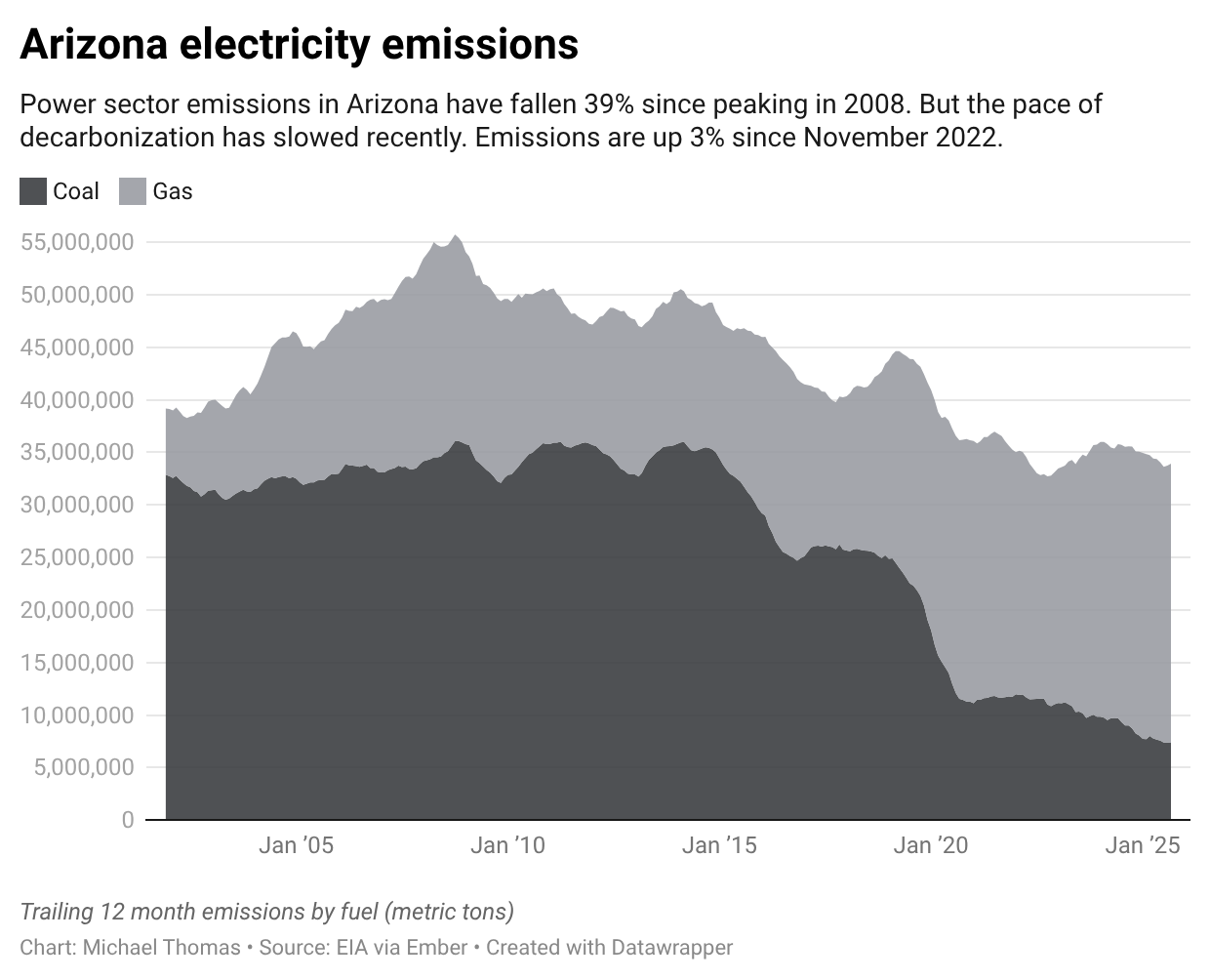

In the last decade, solar power generation has grown by more than 400% in the state. The state has added 4,748 MW of battery storage capacity—equivalent to the peak output of 5 nuclear power plants. That’s helped the state cut its emissions significantly since 2010.

But solar and short-duration batteries provide hardly any power to these machines when it’s 3am. That’s one reason why, after falling for more than a decade, Arizona’s electricity emissions have risen by 3% since ChatGPT launched in November 2022.

The data center surge has driven Arizona utilities to walk back decarbonization commitments. In August 2025, APS abandoned its 2050 "100% clean energy" commitment, replacing it with an aspirational "carbon neutral" goal that allows offsets. The company also eliminated interim targets and extended operations at the Four Corners coal plant to 2038.

Utilities are also planning large investments in natural gas power plants. When it announced that it would renege on its climate targets, APS announced a new planned 2,000 MW gas plant.

“Additional natural gas generation is essential to support our existing customers and to begin addressing unprecedented requests from extra-large energy users, such as data centers,” Tetlow, the company’s CEO, said.

Data center water use has emerged as another flashpoint in Arizona’s arid landscape. “This has been the driest 12 months in 126 years. We are on red alert, and I think data centers are an irresponsible use of our water,” Mesa Vice Mayor Jenn Duff told NBC News.

Some tech giants are responding by eliminating water cooling. Joe Kava, Google’s VP of Global Data Centers, announced the company’s Mesa facility would use no water for cooling. Microsoft has said its data centers “will use zero water for cooling for more than half the year, leveraging a method called adiabatic cooling.”

This will put less pressure on scarce water resources, but it will push electricity demand up even higher. Companies use water cooling more in order to use electric cooling systems less. Take away the water cooling systems and each data center will use more electricity. In a place like Arizona that might be the right choice, but it’s a tradeoff nonetheless.

Some communities have chosen to block data centers altogether.

In December 2025, Chandler’s City Council voted 7-0 to reject a $2.5 billion AI data center despite lobbying from former Senator Kyrsten Sinema. A few months earlier, Tucson’s City Council unanimously halted Project Blue, a proposed $3.6 billion, 600 MW Amazon-linked data center that would have consumed 15% of Tucson Electric Power’s current generation capacity.

“In addition to the water use, this was a problem because of the energy use,” Councilmember Kevin Dahl said.

Tech companies and data center developers continue to push ahead, despite the opposition. Google, Microsoft, Meta, and Apple are all expanding their data center operations in Phoenix.

A proposed 1.5 gigawatt Hassayampa Ranch development backed by investor Chamath Palihapitiya received zoning approval in December 2025. The developer of the project told Fortune, “We have probably six to eight large hyperscalers that are interested in looking at it.”

Thanks for your reporting. The data center boom is the latest assault on any form of sustainability. Furthermore, the selection of desert environments as the sites for these data centers reveals a complete ignorance of the ecological realities in these locations. For example, Phoenix may soon lose a significant portion of the Colorado river water that is currently allocated to the city because the amount of water available from the Colorado river is steadily decreasing due to climate change.

Great analysis. Another piece worth mentioning is the energy use of semiconductor fabs like Intel and TSMC. They are significant users of energy and also operate 24-7. Not on the same scale as data centers (and there are fewer of them), but a contributor to the challenges facing APS and the state as a whole.