Hurricane Helene Revealed the Deep Flaws in American Disaster Insurance

Why many victims of the latest climate disaster won't be covered by insurance

This is the first story in a new series on how climate change is impacting home insurance in America. Become a paid subscriber to get Part 2 and 3 in your inbox and support independent climate journalism.

Hurricanes and tropical storms are generally thought of as coastal affairs. But last week, Hurricane Helene proved that even inland communities are at risk of these increasingly powerful storms.

In Atlanta, 11 inches of rain fell over the course of 48 hours, the most ever recorded. Further north, in Tennessee, record rains nearly burst a federal dam. Dozens of rivers as far as 500 miles inland reported major flooding as a result of Helene.

In Asheville, located in the eastern part of North Carolina, the French Broad River rose by 24 feet, breaking a record. Entire homes were swept away. All roads out of the community were closed for days, with some of them destroyed entirely; many have still not opened.

“To say this caught us off-guard would be an understatement,” Buncombe County Sheriff, Quentin Miller, told CBS News.

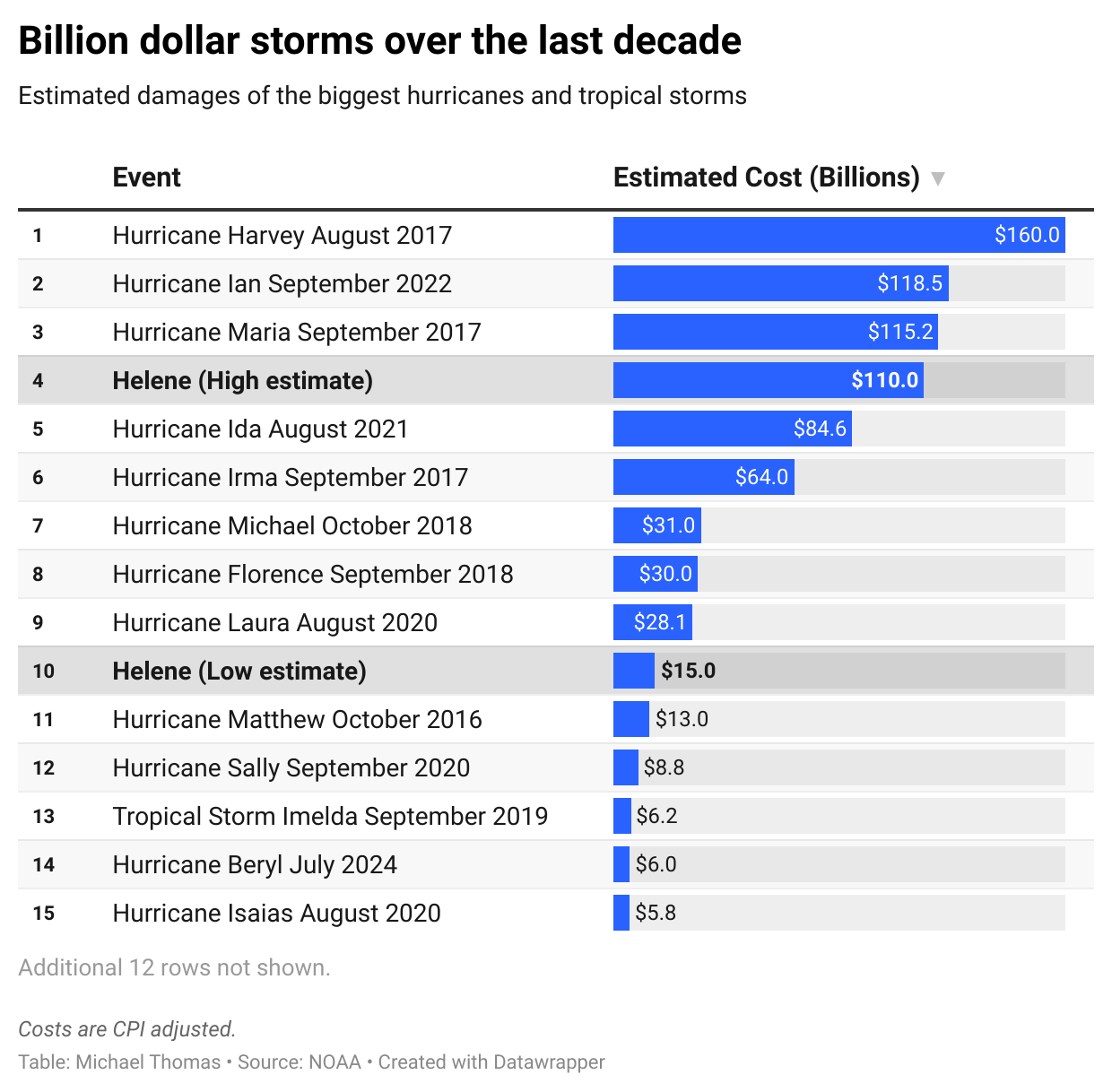

The extent of Helene’s damage and financial cost won’t be known for months. But early estimates suggest it will be steep. Moody’s Analytics expects between $15 billion to $26 billion in property damage. AccuWeather predicted the total damage and economic loss will be between $95 billion and $110 billion. That would make Helene one of the country’s most costly storms over the last decade.

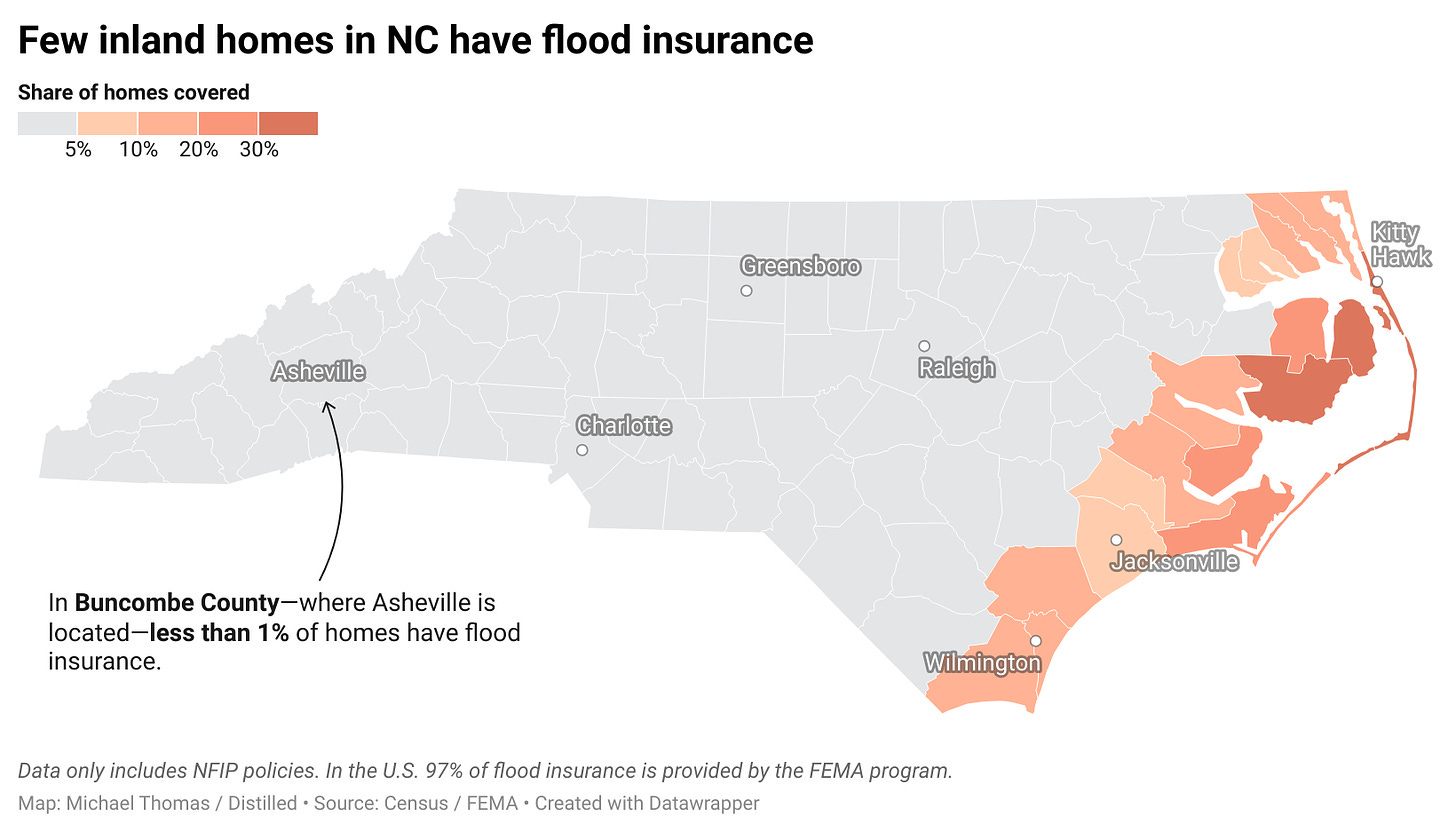

But unlike many hurricanes, much of the damage from last week’s storm won’t be covered by insurance. That’s because so much of the damage happened far inland where few homeowners have flood insurance.

Take Buncombe County, where Asheville is located, for example. The county has 137,123 housing units1. But just 941 of those units—less than 0.7%—have flood insurance through the NFIP, the federal insurance program that issues 97% of the country’s flood insurance plans2.

A recent report found that 16,306 properties located in Buncombe County were at risk of flooding in a 1-in-100 year storm. (Last week’s flood was a 1-in-1,000 year event).

In Rutherford County, known by tourists as the home of Chimney Rock, even fewer people have flood insurance. Just 90 of the county’s 32,967 housing units have flood insurance. The area experienced severe flooding, with main street being wiped out almost entirely.

The same study found that 4,457 properties were at risk of flooding in a 1-in-100 year storm.

North Carolina isn’t an outlier either. No inland county in South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, or any other state hit by Hurricane Helene has a higher federal flood insurance “uptake rate” than 5%.

That’s a problem considering that some of the communities at risk of the most flooding are located far from the coast in Appalachia. In some Tennessee counties, more than 25% of homes are at risk of flooding during major rain events.

Little of this is the fault of homeowners themselves.

For years climate risk experts have been warning that America’s flood insurance system is deeply flawed. According to one of the most advanced modeling efforts conducted by First Street, 6 million homes in the country are at severe risk of flooding and yet are left out of the federal government’s flood risk maps. (More on this below).

The national flood insurance program is also in a deep financial hole. The only way out of it, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is higher insurance rates or more federal debt. The CBO predicts that flood insurance rates will double over the coming years. Half a million Americans will see their rates rise by more than 300%.

Built in the more stable climate of our past, America’s flood insurance system is cracking at the seams as the world warms. Like much of our infrastructure and institutions, it wasn’t built for a rapidly warming world.

In this deep dive on some of the flaws in America’s federal flood insurance program, we’ll look at:

Why floods—already the most costly of natural disasters—are one of the largest sources of climate risk

How the Great Flood of 1927 made a million people homeless and explains why home insurance doesn’t cover flood damage

Why most flood maps are outdated and inaccurate resulting in hidden climate risk

FEMA’s latest effort to fix the NFIP’s $20 billion debt problem—and why it will cause flood insurance rates to double over the next five years

How flood risk threatens the financial stability of Fannie Mae, the largest owner of mortgage debt in America

This is the first in a series of stories that will look at how climate change is impacting home insurance. Become a paid subscriber to read all the stories in the series and support independent climate journalism.