Solar and Batteries Are Squeezing Out Natural Gas in California

The state's power emissions fell 8% last year, even as they rose almost everywhere else.

Earlier this month, I wrote a story about how electricity emissions rose in the US last year, amid rising electricity demand. The growth in emissions was widespread. Power plants pumped out more carbon pollution everywhere from Texas to the Northeast.

But there was one notable exception: In California, carbon emissions fell by 8%.

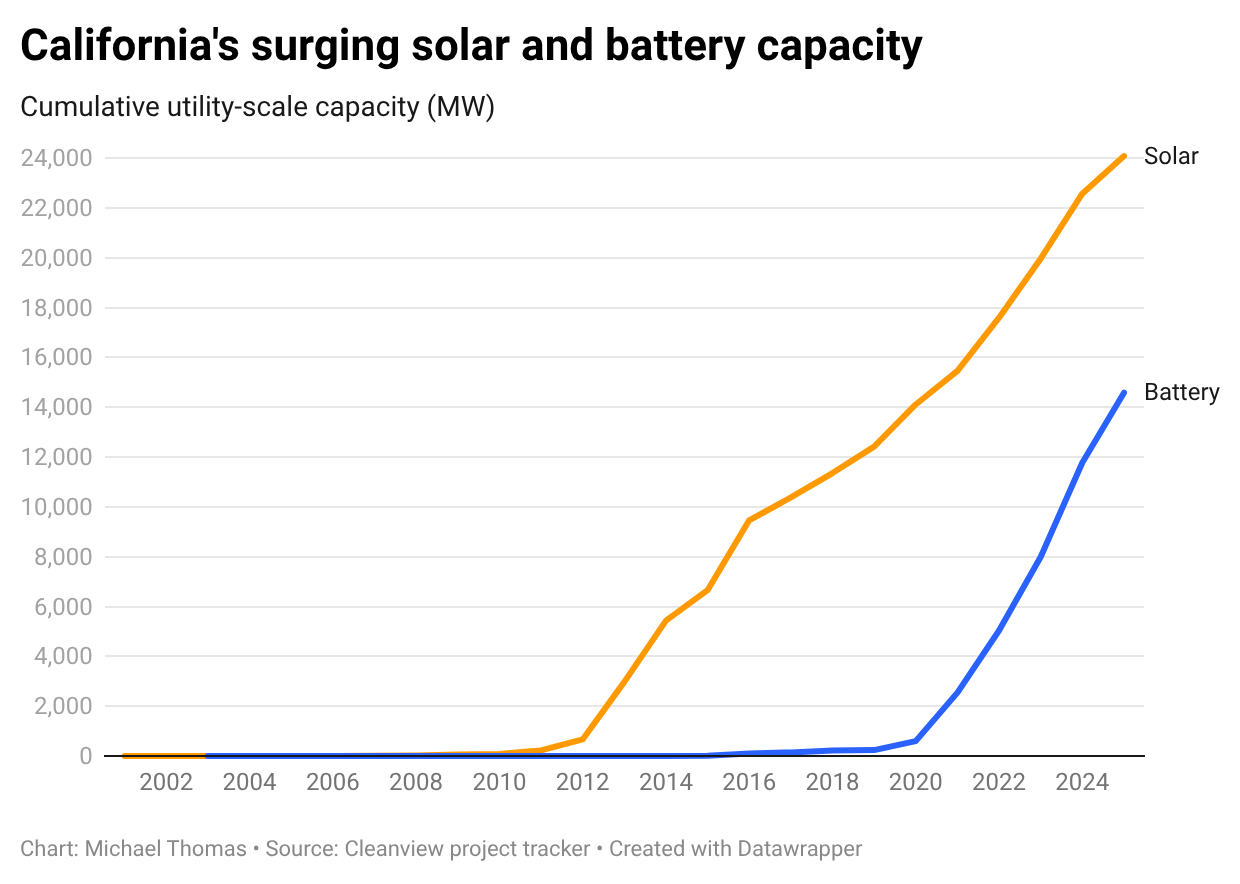

The decarbonization of California’s power grid has been driven by huge growth in solar and battery capacity in recent years. The state has added more than 300 large-scale solar projects and more than 200 large-scale battery projects in the last 5 years, according to Cleanview’s project tracker. Small-scale solar and battery adoption has also been significant.

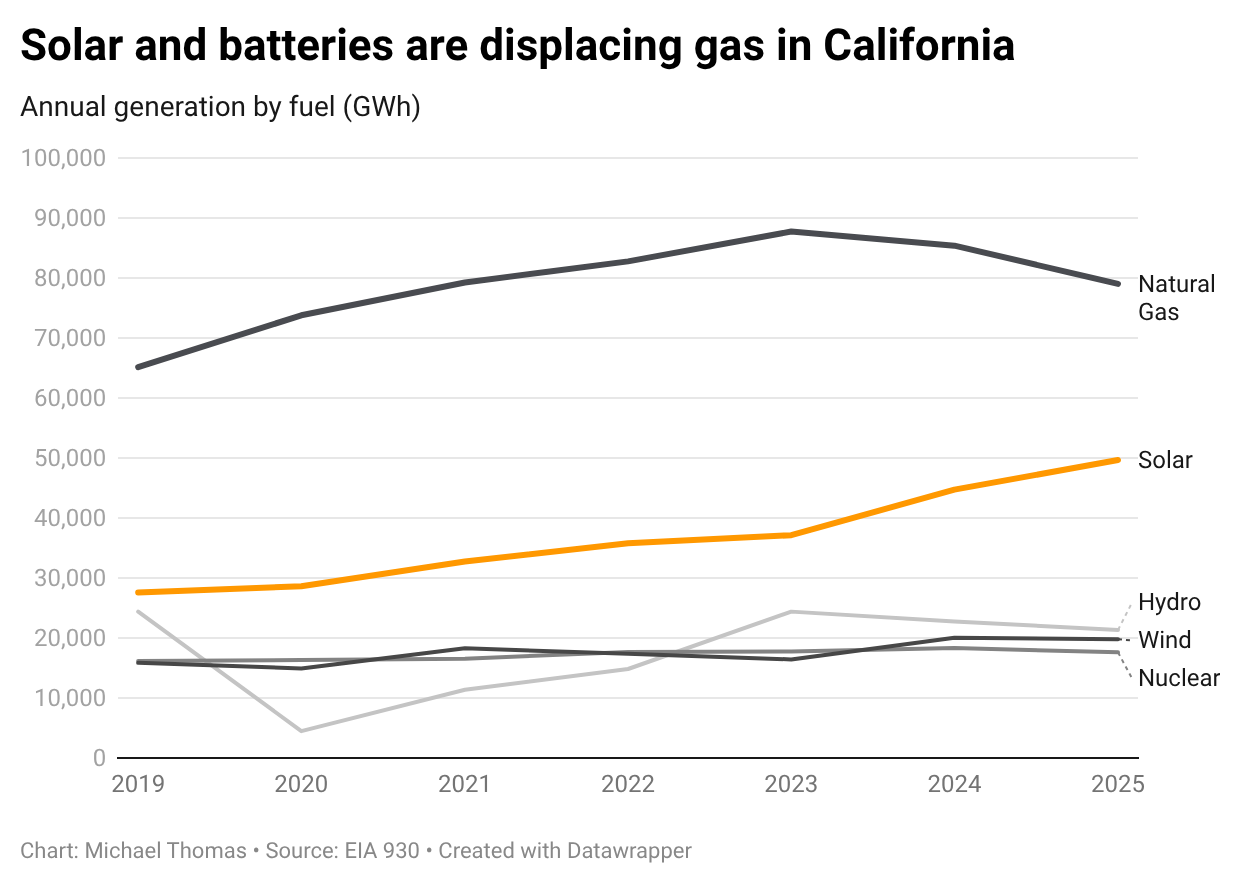

The growth of solar and batteries is now cutting into the state’s fossil fuel power plant generation. Since 2023, natural gas generation has fallen by 10%.

Much of this fossil fuel displacement is happening in the afternoon and evening hours when electricity demand is highest. Batteries that charge up on abundant solar power during the day now discharge during these evening peaks when natural gas peaker plants would otherwise fire up.

The state still has a long way to go in its efforts to reach 100% clean power, but the trends are going in the right direction. That wasn’t true as recently as just a few years ago. The state’s electricity emissions were stubbornly flat for much of the last decade.

The growth of solar and batteries wasn’t the only factor behind California’s decline in emissions last year though. Falling electricity demand also helped. Homes and businesses consumed 2.4% less electricity in 2025 than they did the year before.

Here the state was an outlier, too. On every other major US electric grid—in Texas, in the Midwest, in the Northeast—electricity demand rose. In Arizona, it rose by a staggering 8%. That demand growth, which was driven in many places by data centers, meant that coal and gas plants had to run more frequently.

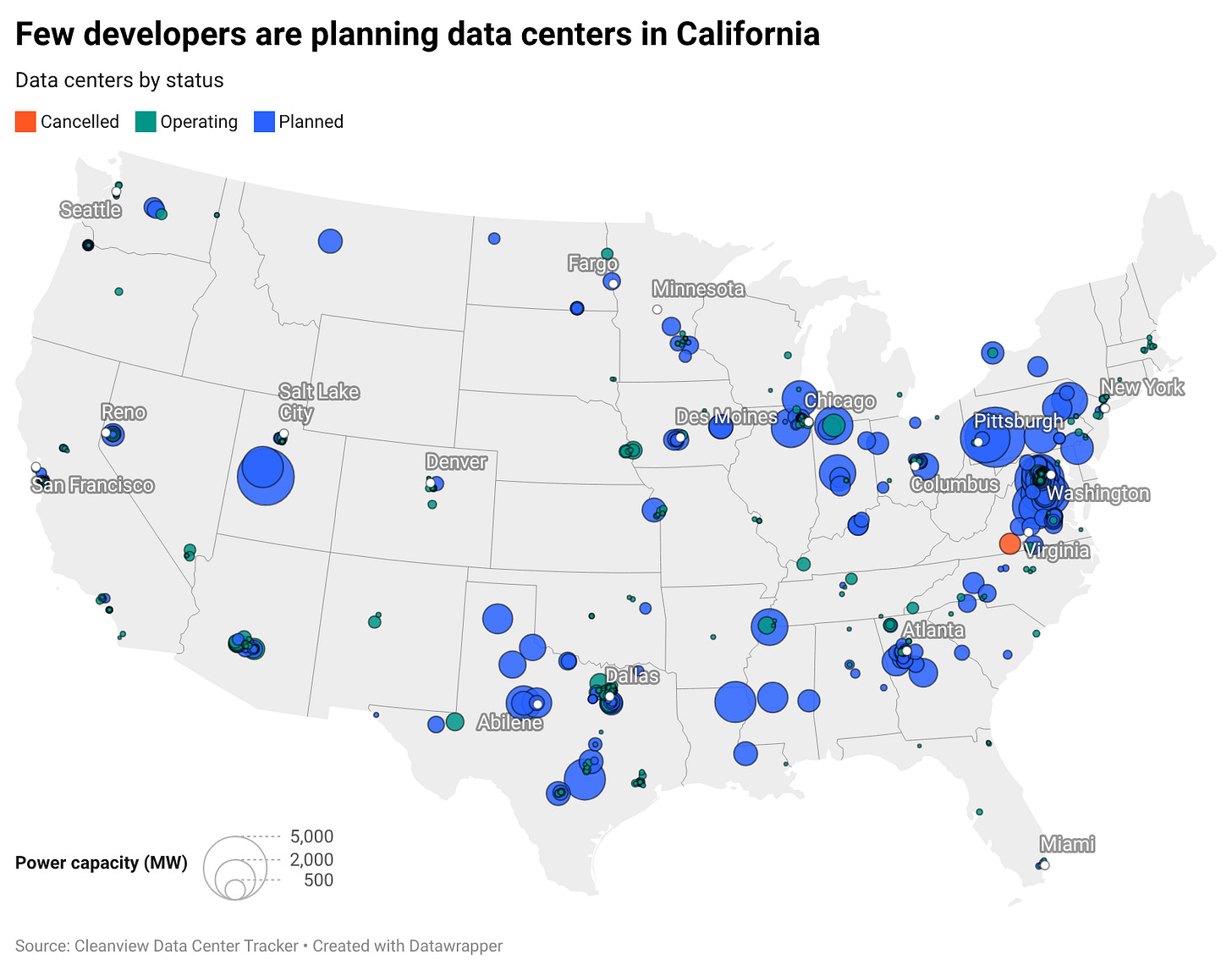

In California there’s been very little growth in data centers or other industrial sources of electricity demand. The state’s high electricity prices and slow permitting process have made it unattractive to hyperscale data center developers. (Slow permitting has also plagued renewable projects for decades, slowing the energy transition).

Here’s a map showing all the planned data centers in the US from our project tracker at Cleanview. Note how few are in California relative to places like Texas, the Midwest, and the Mid-Atlantic.

California’s real test will come when its electricity demand begins to rise again—which is likely in the near future.

The state has ambitious plans to electrify its transportation and buildings, putting millions of electric vehicles on the road and heat pumps in homes. That electrification will be essential to cutting emissions economy-wide, but it will also mean more demand on the grid.

Once demand starts climbing again, California will face the same challenge every other US grid struggled with last year. To decarbonize in that environment will require deploying clean energy even faster.

I live in CA and as near as I can tell the power itself is not that expensive. Even if I buy my power from a third party green provider PG&E will charge something like 35 cents / kWh to deliver that power plus a monthly fee for the privilege of connecting to the grid. We have a fully electric house (not even a gas hookup) and solar panels and a good size battery. For the year we supply more power than we consume.

Great news. Thanks for this. I'd like to see a breakdown of what the data centers are storing and crunching. What percentage is consumer videos, photos, emails, i.e. legacy digital trash. What percentage is corporate. What percentage is AI. What percentage is the never-ending feeds on TikTok, Insta, Youtube, Reels. The more we understand, the more we can give policymakers some levers to pull, placing taxes and incentives in the right places.