Why Wind Energy Is in a State of Crisis

Wind energy's recent woes, explained

It’s been a rough few years for the wind energy industry.

After two decades of steady growth, annual wind capacity additions have fallen for two consecutive years—and not by an insufficient amount. Wind developers in the United States built half as much new wind capacity in 2023 and 2022 than they did in the previous two years.

Three years ago, it seemed like the U.S. had a real shot at hitting Biden’s ambitious target of building 30 gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind. Then came the perfect storm of supply chain bottlenecks, rising inflation, and high interest rates. Since then, offshore wind developers have cancelled more than 7 gigawatts (GW) of planned projects on the East Coast.

The nascent offshore industry isn’t alone in its struggles. Onshore wind, which developers have built at scale since the early 2000s, had its worst year in 2023 in more than a decade.

As the industry’s growth has screeched to a halt, its biggest companies have begun shedding jobs. In May, Siemens Gamesa, one of the largest wind turbine manufacturers in the world announced it would cut 4,100 jobs, 15% of its workforce.

Wind energy investors, bullish on an industry that was expected to grow faster than nearly any other just a few years ago, have been hit hard too. Last year Siemens Gamesa lost $943 million. In 2022, GE Renewable Energy and Vestas—the other two global turbine manufacturing giants—lost $2.24 billion and $1.2 billion respectively.

Then—as if a global pandemic and perfect storm of, ehem, headwinds (sorry) weren’t enough—mother nature rubbed salt in the wound of the U.S. wind industry. In 2023 wind electricity production fell for the first time ever. The cause? An unprecedented decline in wind speeds.

“I’ve been forecasting for 27 years, and it’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen,” Mike Augustyniak, a meteorologist, told Inside Climate News.

Wind’s woes can be hard to see

To some, the extent of the wind industry’s troubles may come as a surprise.

Every day, there are new stories about the unstoppable growth of clean energy. Each month or quarter, a new record is broken and dozens of new carbon-free power projects are brought online. But many writers and pundits group wind and solar together. When you read a story about the growth of clean energy, the odds are good that it’s referencing the aggregate growth of solar, wind, and maybe battery storage.

To offer an example close to home, take the first paragraph of a recent Distilled story that I wrote (emphasis added):

Over the last decade, clean energy capacity has exploded in the United States. The combined capacity of all utility-scale solar and wind projects around the country has grown from 75 gigawatts (GW) in 2014 to just over 240 GW today—a growth of more than 320%.

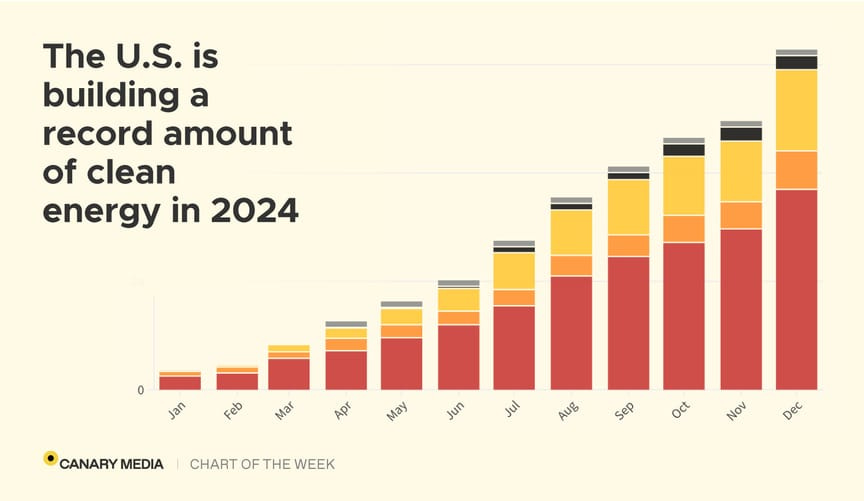

Or look at this recent chart from Canary Media:

Or take another recent story from the industry trade publication, Utility Dive (emphasis mine):

The U.S. utility-scale solar, wind and storage sectors added a total of 5,585 MW in the first quarter of 2024, a 28% increase year-over-year, says a new quarterly market report released Tuesday by the American Clean Power Association.

I cite these three examples—and not mainstream news outlets that have written similar stories—because I want to emphasize that this isn’t an instance of clean energy noobs that don’t know what they’re talking about. Even the most wonky, in-the-weeds commentators group solar and wind together. And for a lot of good reasons, too. Often it makes sense to write about renewables as a whole.

But grouping clean energy generation technologies like this has made it easy for even the most informed climate leaders, policymakers, and advocates to overlook a huge problem: While America is deploying solar and batteries at a staggering pace, it’s wind energy industry is in a prolonged state of crisis.

Wind energy’s perfect storm

No single problem can explain the crisis facing wind energy. Instead, multiple factors have coalesced to form a perfect storm of challenges and setbacks. While some of these challenges have only recently emerged since the pandemic, others have been brewing for much longer.

Unlike utility-scale solar and battery storage, wind energy has been deployed at scale for decades. By 2004, developers in the United States had already built 5,258 megawatts (MW) of wind capacity. By that same year, solar developers had built just under 100 MW—2% as much as their renewable peers.

Wind’s earlier growth came with many benefits. As manufacturers and developers built more turbines and projects, they learned how to reduce costs, which led to more demand, which, in turn, led to further reductions in cost. Wind quickly got on the classic learning curve.

As I wrote in a story last year, wind’s early growth enabled utilities to shut down their dirtiest and most expensive fossil fuel power plants resulting in less emissions and air pollution.

But wind manufacturers and developers weren’t the only ones learning in the early aughts. As wind projects proliferated across America’s Great Plains, NIMBYs and clean energy opponents began developing a playbook to block these projects. By 2012, there was a small, but powerful group of “wind-warriors” and lawyers traveling the country to block wind energy projects.

What started as a group of NIMBYs with varied interests, soon transformed into a national movement with financial backing from the fossil fuel industry. In 2012, American Tradition Institute (ATI), a dark money think tank, organized a convening to discuss a national strategy to change American public opinion about wind energy.

“Public opinion [on wind energy] must begin to change among citizens at large,” a confidential memo, sent to meet attendees, read. The goal of the campaign: “Provide a credible counter message to the (wind) industry.”

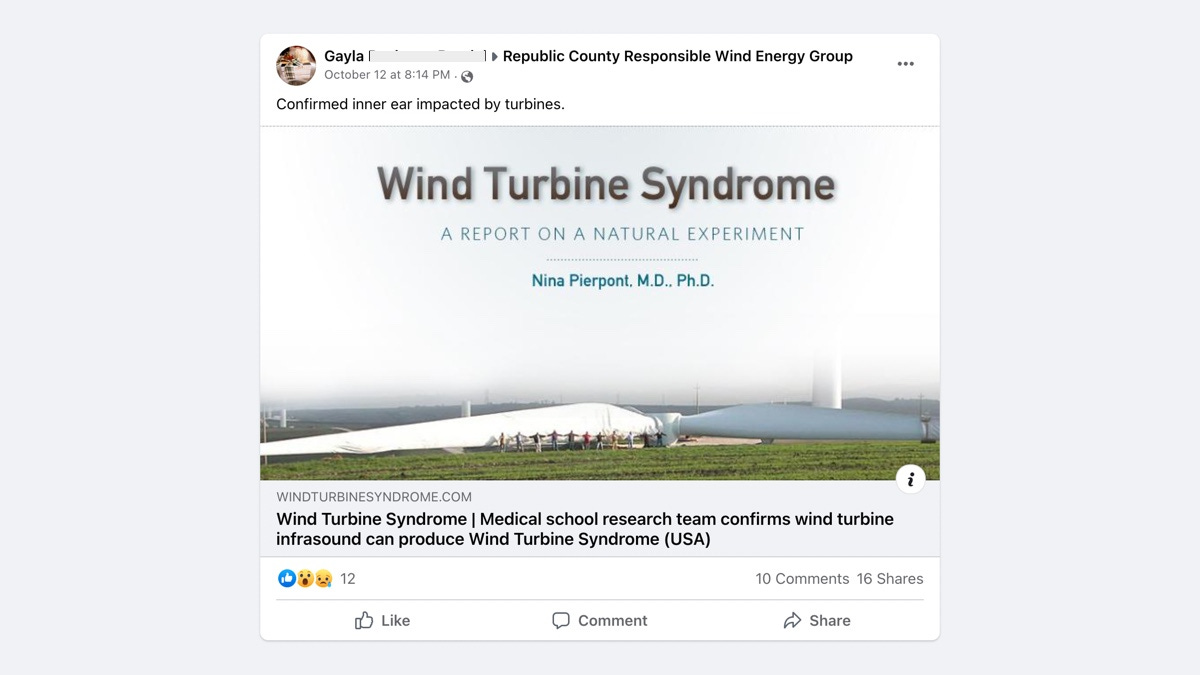

The same year that ATI organized wind opponents in the nation’s capital, Facebook went public and surpassed 500 million active users. The social media platform soon became the anti-wind movement’s greatest weapon. While most traditional media outlets weren’t interested in publishing falsehoods and conspiracy theories about wind energy, Facebook had no system to prevent such ideas from spreading to millions of users.

In 2022, I found nearly 50 Facebook groups dedicated to blocking wind energy projects. The groups were littered with misinformation and misleading claims about wind turbines. For example, many of them contained links to a debunked conspiracy theory that wind turbines cause cancer.

One of the great themes and lessons of the Post-Trump era is that ideas that spread online are rarely contained to the digital world. Few have felt this truth more intensely than wind energy developers.

Dahvi Wilson, who worked on public affairs for one of the largest wind developers in the country from 2012 to 2023, told me that she saw opposition to projects explode during her decade-long tenure at Apex Clean Energy.

A recent study by clean energy researcher, Leah Stokes, and a group of co-authors, backs up Wilson’s claim. In 2000 just under 10% of wind projects saw local opposition. By 2016, nearly 25% of projects had opposition.

Over the last 5 years, a third of all wind projects have been cancelled, according to a January 2024 study by Berkeley Lab. Half of all projects have been delayed by more than 6 months. Local opposition was one of the primary factors in these project cancellations more than 60% of the time.

How the pandemic made everything worse

The pandemic was the straw that ultimately broke the wind industry’s back. It was the worst case scenario that even the most pessimistic risk models didn’t anticipate.

First, the supply chains broke. While most Americans were fighting over the last roll of toilet paper in the aisles of Target, wind manufacturers and developers were fighting over steel components and turbines.

Then came inflation, unlike anything the world had seen in 50 years. A shrinking supply of components and materials caused the average price of wind turbines to shoot up by 40% between 2020 and 2022.

If it had just been supply chain bottlenecks and inflation, the industry may have weathered the storm. But these problems beget another problem: rising interest rates. Central banks efforts to curb inflation hurt the wind industry more than almost any other.

One of the blessings of wind energy is that the fuel is free. God grants it with each gust. But the capital required to build something capable of turning this free wind into electrons comes at a cost. If you add up the costs of a traditional fossil fuel power plant over 30 years, it’ll be almost all fuel costs and little capital expenses. Do the same accounting for a wind project and you’ll get the opposite result: Free fuel and expensive capital.

The price of this capital—in the form of interest rates—is always changing. For decades the wind industry got used to tiny shifts in these prices. In 2019, every developer had a big spreadsheet that made certain assumptions about how much these prices could change. Anyone who experienced the shock of 20% interest rates in the 1980s might have written down some pretty extreme scenarios in their models of the future just in case. The problem is that no one was building wind turbines in the 1980s.

As interest rates soared in 2022 and 2023, all the models broke and many wind developers were left out to dry. Most projects were backed by loans that were in turn backed by long term offtake agreements—basically 15 to 30 year power contracts. The problem was that these offtake agreements were fixed and based on assumptions of a couple percent inflation each year, not a 40% jump in turbine prices in two years. As a result, many developers had to cancel projects and take huge losses.

High interest rates and local opposition also conspired with one another, multiplying the total impact.

Ørsted, one of the largest wind developers in the world, originally planned to finish its Skipjack Wind project off the coast of Deleware in November 2022. But, as I detailed two years ago, the project was targeted by one of the most coordinated and sophisticated anti-wind efforts in the country with backing from a group funded by the largest oil companies.

Caesar Rodney Institute—who counted the nation’s largest oil trade group as a major donor at the time—sent letters out to 35,000 coastal homeowners claiming that Skipjack Wind would cause property values to plummet by 20 to 30%. Hundreds of residents called their mayors, state senators, and other representatives. The tactic worked. After failing to get the permits required to build a substation, Ørsted announced it wouldn’t be able to finish the project until at least November 2026.

In a pre-pandemic world, a four year delay would have been painful, but not catastrophic. In a world of high interest rates, it was a death knell.

Interest rates are often described as the cost of money. When a developer borrows $1 billion to build a megaproject, they are renting that money from the bank in the same way that many American homeowners rent money in the form of a mortgage. But interest rates can also be described as “the price of time.”1 This idea is captured in the cliche that “time is money.” As time grows, so does the burden of interest—often exponentially so. This is what kills projects.

In January of this year, Ørsted cancelled its Skipjack Wind project saying it was no longer economically viable.

An uncertain future

Over the next 12 months, developers plan to build 5.3 GW of new wind capacity. That’s roughly a third of the capacity built in 2022 and 2023. It’s a fraction of the 34.4 GW of utility-scale solar capacity that is expected to come online during that period.2

There are signs of hope on the horizon for the wind industry though. The Federal Reserve is expected to cut interest rates next month for the first time since they began their war on inflation. Permitting reform—which would make it harder for a small group of NIMBYs to block projects with wider public benefits—is having a moment in Congress. Offshore wind projects that survived the storm are nearing completion and new ones are getting started.

It’s not hard to imagine a future where the pandemic and its aftermath were just a small blip in a larger arc of growth. But it’s also not hard to imagine a more troubled future for wind energy.

Between 1970 and 1980, nuclear energy capacity in America grew by a factor of 7. For a time, it’s growth seemed unstoppable. Futurists imagined a society powered by atoms with no need for fossil fuels. That future didn’t materialize. Over the next decade, the cost of nuclear energy ballooned, public opinion soured, and growth ground to a halt.3 25 years later, the industry still hasn’t recovered.

Wind turbines and nuclear power plants are very different technologies. But they exist in the same uncertain and volatile world. And in that world, no technology’s future is guaranteed.

I’m borrowing this definition from Edward Chancellor’s book The Price of Time: The Real Story of Interest.

The cause of nuclear energy’s troubles and these cost increases are hotly debated. But that nuclear energy stopped growing in America is a matter of fact.

As a consultant I started permitting wind projects in 2001 and have worked on projects throughout the Western States. I agree with much of your analysis, but I think another factor is lack of transmission especially in high wind areas. I also think there is a lot of opportunity for repowering old wind projects. The largest wind project by number of turbines in Washington state still has 0.66 MW turbines. Many wind projects in the U.S. are 15-20 years old and should be good candidates for repowering.